Julie Mehretu

How to Use Exhibition Guides

Swipe right to advance through the guide |

Julie Mehretu

Add content

Julie Mehretu

Early Works

In early paintings such as these, Mehretu explored how to represent the cumulative effect of time by layering materials: she embedded her character map drawings between strata of poured paint, creating fossilized topographies. While Untitled (two) and Map Paint (white) consist of these drawings of flattened landscapes, in Untitled (yellow with ellipses), Mehretu introduces transparency, color, graphic elements, and multiple perspectives.

Julie Mehretu

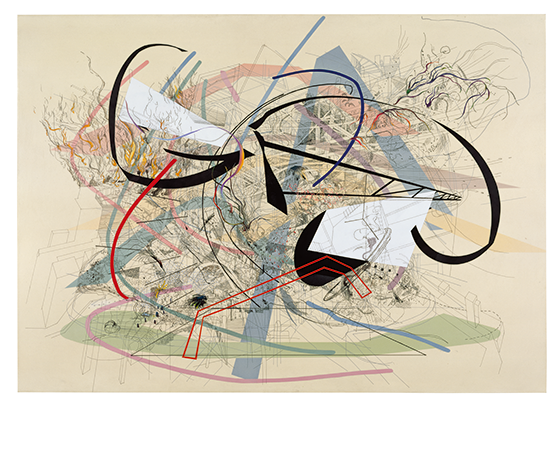

Babel Unleashed, 2001

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis T. B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 2001

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Walker Art Center

In her work from the early 2000s, Mehretu reimagined the type of ordered space typically found in traditional European painting. She combined layers of buildings, explosions, and graphics from transit systems and airport terminals in Babel Unleashed, creating a micro-cosm of a metropolis, “full of migrants in transit, people walking by, through, past, and with each other.” For Mehretu, transit suggests the movement of both people and perspective: the staircase, for example, could represent ascent, but could also draw the viewer into the composition.

Julie Mehretu

In Stadia II (left) and Black City (right), Mehretu interrogates sports and military typologies to disrupt modern conceptions of leisure, labor, and order. The coliseum, amphitheater, and stadium in Stadia II represent spaces that are designed to situate and organize large numbers of people but also contain an undercurrent of chaos and violence. While Stadia II is filled with curved lines and a panoply of pageantry—flags, banners, lights, seating—Black City is more linear and contains references to the military and war, such as general stars and Nazi bunkers. Both works call attention to the ways in which modern culture and the spectacle of contemporary wars—including the War on Terror and the Iraq War—are connected to imperialism, patriarchy, and power.

Julie Mehretu

Berliner Plätze, 2009

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Commissioned by Deutsche Bank AG in consultation with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation for the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Kristopher McKay

While living in Germany in 2008, Mehretu grew increasingly critical of American foreign policy, particularly the Iraq War and the War on Terror. In Berlin, she was surrounded by visible scars of the Holocaust and the Cold War, which pushed her to question her role as an American who opposed the war but nonetheless felt responsible for the terrors afflicted on Iraqi civilians and spaces. Seeking to develop a counternarrative, Mehretu began to incorporate techniques of erasure, opacity, and overwriting into her art practice. In Berliner Plätze, drawings of buildings mostly eradicated by bombings during World War II form a hazy gray field.

Julie Mehretu

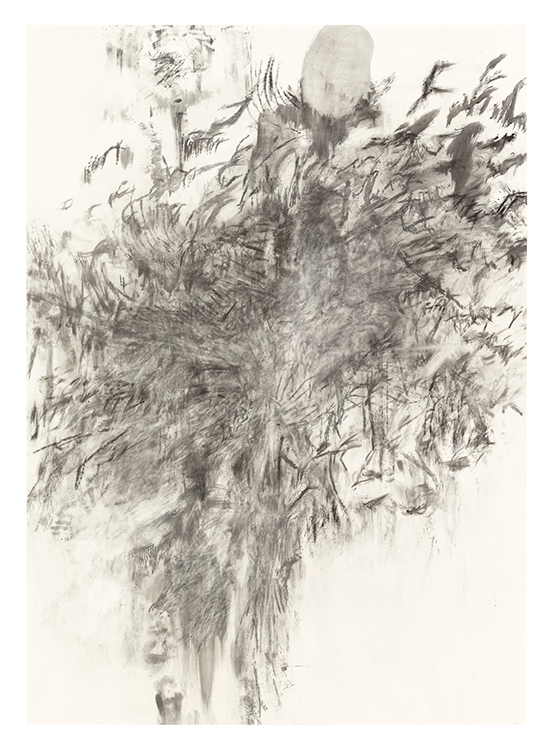

Being Higher II, 2013

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Collection of Susan & Larry Marx, courtesy of Neal Meltzer Fine Art, New York

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Tom Powel Imaging

In 2013, deeply affected by the Syrian civil war, the spread of the Arab Spring, Hurricane Sandy, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, Mehretu began to move away from architectural drawing and instead use mark making and gesture to further explore violence, resistance, and struggle in her work. For the first time, she incorporated human-scaled figures into her compositions, began to work with new tools, and used her bare hands to push and pull paint. In both Being Higher I and II a body appears to be hovering among a variety of gestural marks that Mehretu made by swiping, patting, and even slapping the canvas.

Julie Mehretu

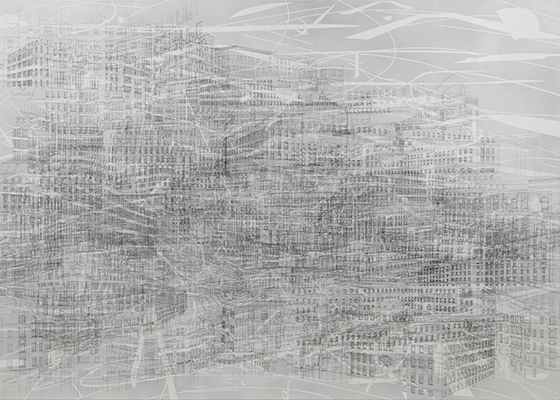

Invisible Line (collective), 2011

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Pinault Collection

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Ben Westoby

In Invisible Line (collective), Mehretu presents a densely layered perspective of New York, combining historic, present-day, and unbuilt architectures and both pedestrian and aerial views of the city. By amalgamating these buildings and sightlines, she reduces the metropolis to a gray haze, drawing a connection between architecture and ruins and suggesting the blur of history and time and the buzz of the masses. Mehretu worked feverishly on this painting during the eighteen days of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, which she followed on an Al Jazeera livestream in her studio. She was especially inspired by the massive public protest that brought down Hosni Mubarak, one of Africa’s longest serving dictators.

Julie Mehretu

In her Invisible Sun paintings, Mehretu moves away from the focus on the city and architecture that characterized her earlier work and instead concentrates on the creative mark and invention itself. Staccato markings and paint smudges resemble graffiti, calligraphy, and even musical notation. Mehretu’s liberated, loose, monochromatic strokes flow over the edges of their canvases, recalling prehistoric cave paintings and suggesting a wide range of possible forms.

Julie Mehretu

Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson, 2016

Ink and acrylic on canvas

The Broad Art Foundation

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Cathy Carver

As its title suggests, Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson links disembodied anatomy with a site of violence and political strife. This painting began with a blurred photograph of an unarmed man with his hands up facing a group of police officers in riot gear, which was taken during the protests that followed the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Mehretu layered color over a blurry, sanded black-and-grey background: fuchsia and peachy-pink areas rise from below, while toxic green tones float above, like distant skies drawing near. Outlines of eyes, buttocks, and other body parts appear within the graffiti-like marks and black blots that hover over smoky areas, suggesting human activity obscured.

Julie Mehretu

Hineni (E. 3:4), 2018

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Don de George Economou, 2019, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Tom Powel Imaging

In many of her recent works, Mehretu has confronted extreme global events and their impact on our senses of time, space, and presence. She based Hineni (E. 3:4) on an image of the 2017 Northern California wildfires, while also exploring the burning of Rohingya homes in Myanmar as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing. The word “hineni” translates to “here I am” in Hebrew, which was Moses’s response to Yahweh (God), who called his name from within the burning bush to tell him he would lead the Israelites in the Exodus to the promised land. By interrogating three types of fires in this painting—one environmental, one intentional, one prophetic—Mehretu explores the contradictory meanings of a single elemental force.

Julie Mehretu

In her most recent paintings, Mehretu introduces bold gestural marks and employs a dynamic range of techniques such as airbrushing and screenprinting. The works draw on her archive of media images of major global events such as environmental catastrophes, wars, crises, protests, and abuses of power; she digitally blurs, crops, and rescales this source material, then uses it as the foundation for her paintings, overlaying the images with calligraphic sweeps and loose drawing. Of the blurred photographs, Mehretu says, “There’s a subconscious terror that you feel vibrating close to the surface.… More than I’ve ever felt in my lifetime here in the U.S. It’s seeping into everything. I feel like that is what I’m trying to metabolize in these new paintings.”

Haka (and Riot), 2019

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Andy Song

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Tom Powel Imaging

For the diptych Haka (and Riot) Mehretu began with photographs taken inside detention facilities in Texas and California where undocumented migrant children have been detained. The artist blurred and abstracted these images with layer upon layer of digital and physical drawing, painting, airbrushing, and screenprinting, creating a distorted space filled with voids resembling sunken eyes, skulls, and orifices. These cavities seem to coalesce into a powerful, colossal form that suggests exorcism or a dancer performing the haka, a Māori war dance.

Julie Mehretu

Drawing is central to Mehretu’s practice, and the works on paper in this gallery serve in part as an index of the marks that appear in her paintings. They include prints in etching, aquatint, and engraving as well as more gestural and fluid compositions in watercolor and ink that anticipate the figurative elements in some of her more recent paintings. Many painters cover over their preliminary sketches, but Mehretu has always allowed her drawings to remain exposed. “As I continue drawing,” she observed in 2002, “I find myself more and more interested in the idea that drawing can be an activist gesture. That drawing—as an informed, intuitive process, a process that is representative of individual agency and culture, a very personal process—offers something radical.”

Haka, 2012

Julie Mehretu Ethiopia, b. 1970, active United States

One-color etching with chine colle

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Gemini G.E.L., LLC

M.2018.206.3

© Julie Mehretu and Gemini G.E.L. LLC, photo: Gemini G.E.L.

The Three Trees, 1643

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Netherlands, 1606–1669

Etching, engraving, and drypoint

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Fund

58.31

Mehretu has worked in printmaking since she was a graduate student. The methodical process of making prints, which includes decisions about line, weight, color, and layering, has informed her painting practice. “Lots of small marks have power,” she has explained, hinting at the social and political implications at the root of her approach to abstraction.

In Rembrandt’s iconic etching The Three Trees, numerous curlicues suggest foliage, while dense crosshatches evoke shade. In Haka, titled after a Māori war dance, Mehretu echoes Rembrandt’s monochromatic palette of stra nds, dots, and dashes, but uses them to evoke an action rather than to describe a landscape. The thin lines that resemble rain in the Rembrandt work take on a cosmic force in Haka, becoming interchangeably celebratory and catastrophic.

Julie Mehretu

Mehretu often incorporates maps into her work in order to interrogate how political boundaries affect individual and collective identities. For the artist, whose personal history has been shaped by periods of migration—from Addis Ababa to East Lansing, New York, Berlin, and beyond—this practice has allowed her to “make sense of who I was in my time and space and political environment.”

In the mid-1990s Mehretu developed her own idiosyncratic system of mapping that includes “characters” such as marks, dots, circles, crosses, arrows, and barbells, and even organic forms like eyeballs, insects, wings, and beaks. She then placed these characters into compositions in which they resemble migrating masses or moving boundaries. As the work developed, she mixed the characters with others to make new clusters and cities, eventually saturating the surface with invented narrative.

Julie Mehretu

GDGDA, 2011

Tacita Dean

United Kingdom, b. 1965, active United States

Two 16mm color films, mute, looped

4 minutes; 3 minutes

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris; Frith Street Gallery, London With: Julie Mehretu and Erika Fortner, Cormac Graham, Eric Kuhl, and Damien Young; camera: Tacita Dean; assistant: Ariane Pauls; rushes: Geyer, Berlin; neg cut: Reel Skill Film Cutting Ltd; first printed by: Soho Film Lab, London, with thanks to Len Thornton; installation: Kenneth Graham, KS Objectiv; originated on: Kodak Motion Picture Film; with thanks: Julie Mehretu and her studio assistants, Jessica Rankin and Mathew Hale; filmed on location at Julie Mehretu Studio, Ludwig Loewe Höfe, Berlin

© Tacita Dean

In GDGDA Tacita Dean captures Mehretu working in her studio, offering spectators a glimpse into a practice that is often shrouded and solitary. The camera looks over Mehretu’s shoulder as she works deliberately and intensely on Mural, a monumental corporate commission, in Lower Manhattan; “GDGDA” translates to “wall” or “mural” in Amharic, one of the Semitic languages of Ethiopia.

With this and similar works, Dean endeavors to create a new kind of biographical film, based on observation rather than narration. Simultaneously, she carries on the tradition of artists documenting one another in the midst of creation.

Julie Mehretu

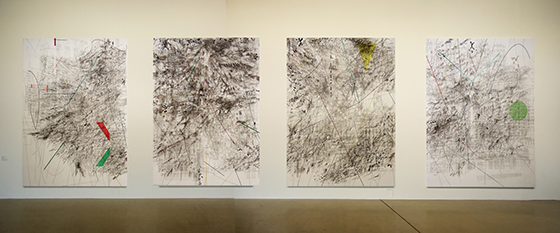

Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts), 2012

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Part 1 of 4: Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

Part 2 of 4: High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Alfred Austell Thornton in memory of Leila Austell Thornton and Albert Edward Thornton, Sr., and Sarah Miller Venable and William Hoyt Venable, David C. Driskell African American Art Acquisition Fund, Dr. Lurton Massee Jr. Endowment for Contemporary Art, the Blonder Family Acquisition Endowment Fund, Robert O. Breitling, Jr. Acquisition Endowment Fund, WISH Foundation Fund of the Community Foundation for Greater Atlanta and through prior acquisition from Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Liberman, Anne and William J. Hokin through the 20th Century Art Acquisition Fund, Henry B. Scott Fund, Jean Cloupsy, Mrs. Elizabeth Fisher, Charles Green Shaw, Jean Gorin Estate, David Kenney, 20th Century Art Acquisition Fund, Judith Alexander, Dr. Milton Mazo to mark the retirement of Gudmund Vigtel, Sidney Singer, Mr. and Mrs. L. Slann, Southeastern Annual Exhibition Purchase Award, Patricia N. Whitlow, Doris Caesar, Mrs. Edith Flynn, Mr. and Mrs. Gerald D. Kohs, J. J. Haverty Memorial Fund for the J. J. Haverty Collection, Scientific-Atlanta, Inc., through the 20th Century Art Acquisition Fund, William Quinn, Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Allison, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Amisano, Mr. and Mrs. Overton A. Currie, Mr. & Mrs. Robert L. Steed, and Mr. and Mrs. G. Kimbrough Taylor, Jr., Dr. and Mrs. Gilbert J. Rose, Mr. and Mrs. Maurice Hahn, Friends of Jon Carsman, Mr. Andrew J. Crispo, Dean Gardens, Wellington Management/Thorndike Doran, Paine and Lewis Collection, Friends of Con- temporary Art, Bruce and Lisa Stein, Rich’s, Andres J. Escoruela, Lawrence Fox for the Ralph K. Uhry Collection, Friends of W. Dean Gillette, Benjamin Elsas, Glenys and Kermit Birchfield, Friends of Henry Toombs, Atlanta Watercolor Club Annual Purchase Award, Jose Pinal, Estate of Theresa B. Oppenheimer, Chester and Claudia Carter, Shirley and Victor Kramer through the 20th Century Art Acquisition Fund, James Twitty, through prior acquisition from Lewis Beck, funds from Kidder, Peabody & Co., Inc./GE Capital Corporate Finance Group through the Kidder, Peabody & Co., Inc. Regional Purchase Program, Dr. Lawrence Rivkin, Jova/Daniels/Busby in celebration of their 20th anniversary, and Joseph Felice Brivio 2013.31

Part 3 of 4: Tate, purchased with funds provided by Tiqui Atencio Demirdjian and Ago Demirdjian, Andreas Kurtz and the Tate Americas Foundation 2014

Part 4 of 4: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2013.458

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Ryszard Kasiewicz

The 2011 Egyptian revolution—part of the “Arab Spring” of uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa—was a major inspiration for this four-part painting and Cairo, installed in the outer gallery. Mogamma is named after an Egyptian government administrative building on Tahrir Square, which was seen as a symbol of modernism and the country’s liberation from colonial occupation when it was first built in 1949, but was later associated with government corruption and bureaucracy before eventually serving as the backdrop to a revolutionary site.

Mehretu began work on these four vertical canvases by exploring the densely layered environment of Tahrir Square, where a dizzying array of architectures—including structures built in Mamluk, Islamic, European, and Cold War styles—coexist. She created a web of drawings that conflate the Brutalist architectural style of the Mogamma with details from other public squares associated with the revolutionary fervor of the Arab Spring, such as the amphitheater stairs and spiraling lights of Meskel Square in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and the mid-century high-rise buildings surrounding Zuccotti Park in New York. She also integrated drawings of globally iconic sites of public protest and change, such as Red Square in Moscow, Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the Plaza de la Revolución in Havana, and Firdos Square in Baghdad.

Julie Mehretu

These three works comprise Mehretu’s first painting cycle. She made Retopistics (center)—her first large-scale, wide-angled perspective on a dynamic, invented space—by layering various architectural histories, maps, and diagrams of airports and transit. In the artist’s words, it shows “a staircase ascending here, another descending into tops of a tent city there; it’s all drawn diminutively, from multiple perspectives and aerial views, with super, super tiny clusters of civilizations, worlds and cities inside this infrastructure of this other meta-space.” The characters in Renegade Delirium (left) seem to be spinning inside an imploding system, while those in Dispersion (right) are propelled off the edges of the canvas, representing the aftermath of the collapse.

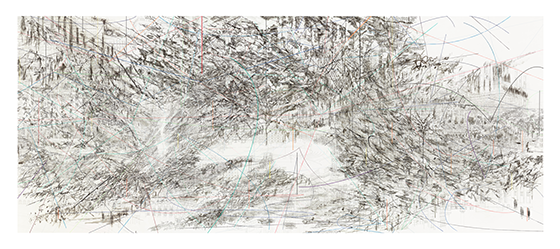

Julie Mehretu

Epigraph, Damascus, 2016

Photogravure, sugar lift aquatint, spit bite aquatint, and open bite on six panels

Edition 13 of 16 + 2 AP

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Kelvin and Hana Davis through the 2018 Collectors Committee

M.2018.188a–f

Printed by BORCH Editions, Copenhagen

© Julie Mehretu

Epigraph, Damascus is a major achievement in printmaking for Mehretu, representing a new integration of architectural drawings and painting overlaid with an unprecedented array of marks. Working closely with master printer Niels Borch Jensen, Mehretu used photogravure, a nineteenth-century technique that fuses photography with etching. She built the foundation of the print on a blurred photograph layered with hand-drawn images of buildings in Damascus, Syria, then composited that together with a layer of gestural marks made on large sheets of Mylar. On a second plate, Mehretu executed her characteristic variety of light-handed brushstrokes, innovatively using techniques known as aquatint and open bite. Describing the interplay of architectural details and mark making in this work, Mehretu says, “You have the skeleton of the ghosts of Damascus, and then you have the blur, the haze, or breakdown of the ongoing civil war.”

Julie Mehretu

Transcending: The New International, 2003

Ink and acrylic on canvas

Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, T. B. Walker

Acquisition Fund, 2003

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Walker Art Center

This painting began with a map of Ethiopia’s capital city, Addis Ababa, which Mehretu fused with maps of other African economic and political capitals, creating a vast network of aerial views of the continent. In subsequent layers she included drawings of both colonialist architecture in Africa and iconic modernist buildings erected there during and after liberation. In the center of the painting Mehretu layered drawings of the many African plazas of independence with idiosyncratic markings she has called “characters.” Here, these characters stage battles, migrate, form alliances, congregate, and ultimately participate in a system of entropy.

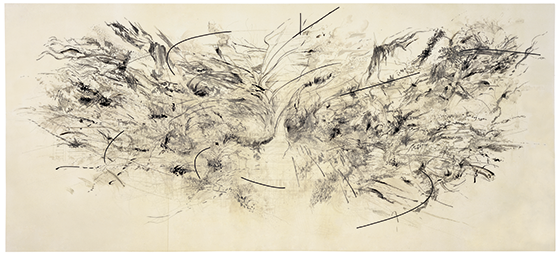

Julie Mehretu

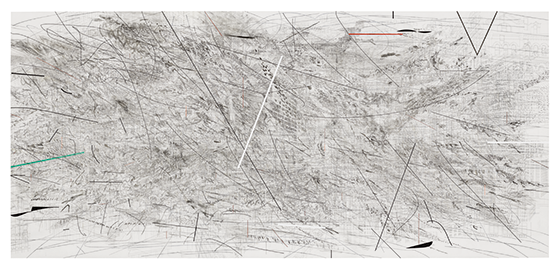

Cairo, 2013

Ink and acrylic on canvas

The Broad Art Foundation

© Julie Mehretu, photo: Tom Powel Imaging

Mehretu has periodically painted large, horizontal canvases full of layered drawings—like the four in this gallery—to address complexities of scale, size, detail, and expanse. These panoramas often address monolithic histories, such as twentieth-century modernism and the African liberation movements of that time.

She painted Cairo after spending time in the city in the days following Egypt’s first democratic election. The painting explores Tahrir Square, which millions of protesters occupied for eighteen days in 2011, from multiple diffracted vantage points. Mehretu based the composition on an array of images such as aerial maps, her own photos, and a bus map that became the main artery inside the painting. The resulting work seems to vibrate and spin, suggesting the passage of time and the movements of millions of bodies during the uprisings.

Julie Mehretu

This exhibition was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Major support is provided by

![]()

Sponsored by Max Mara and Phillips.

Generous support is provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, carlier | gebauer, Marian Goodman Gallery, and White Cube. Additional support is provided by Visionary Women.

All exhibitions at LACMA are underwritten by the LACMA Exhibition Fund. Major annual support is provided by Kitzia and Richard Goodman and Meredith and David Kaplan, with generous annual funding from Terry and Lionel Bell, Kevin J. Chen, Louise and Brad Edgerton, Edgerton Foundation, Emily and Teddy Greenspan, Marilyn B. and Calvin B. Gross, Mary and Daniel James, David Lloyd and Kimberly Steward, Kelsey Lee Offield, Mr. and Mrs. Anthony and Lee Shaw, Lenore and Richard Wayne, Marietta Wu and Thomas Yamamoto, and The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation.