|

1

|

Charles L. Griffin, Scranton, Pennsylvania

Toddler with dog, c. 1892

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

The introduction of faster film emulsions and electric light in the 1890s made it easier to photograph toddlers and pets, leading to a fad for light-filled cards like this one.

|

|

2

|

William A. Fermann, Stoughton, Wisconsin

Baby, c. 1888

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

3

|

W. A. Wilcoxon, Bonaparte, Iowa

Baby, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

The mass production of consumer goods in the late nineteenth century led to a broad expansion of the middle class and a related desire to show off the trappings of economic comfort. Here, a baby is photographed sitting on a scale rather than in its mother’s lap.

|

|

4

|

Julius Caesar Strauss, St. Louis, Missouri

Man with baby, 1892

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

5

|

W. A. White, Wilson, Kansas

My First Baby Friend Tompie and His Pet, 1896

Collodion silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

|

|

6

|

William Henry Cobb, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Toddler, c. 1890

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

7

|

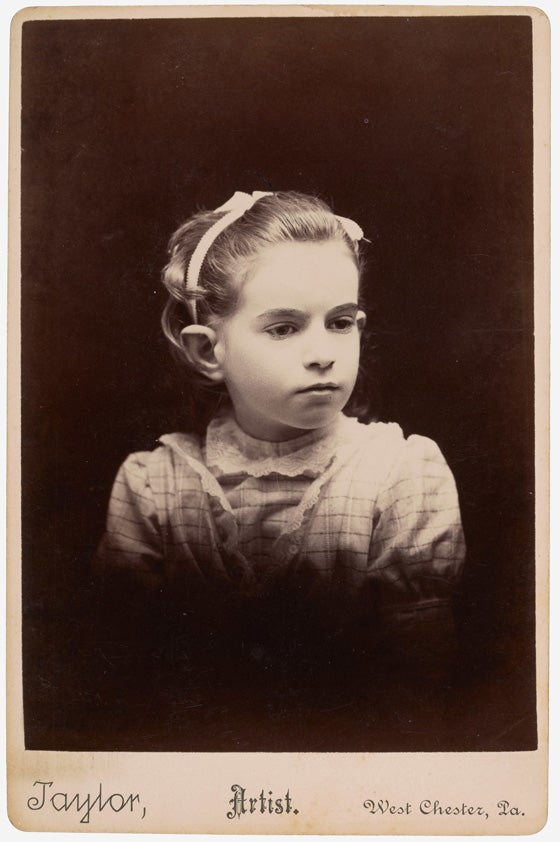

Morrill [and] Lowell

Three-and-a-half-year-old girl, n.d.

Albumen silver print

William L. Schaeffer Collection

|

|

8

|

Samuel Logan, Fargo, Dakota Territory

Willie Poten, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

9

|

C. H. Wareham, Freeport, Illinois

Boy, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

10

|

Halsted and Kehm, Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Sisters sharing photographs, late 1880s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

These two girls humor the photographer as they pretend to look through cabinet cards that presumably show their family and friends.

|

|

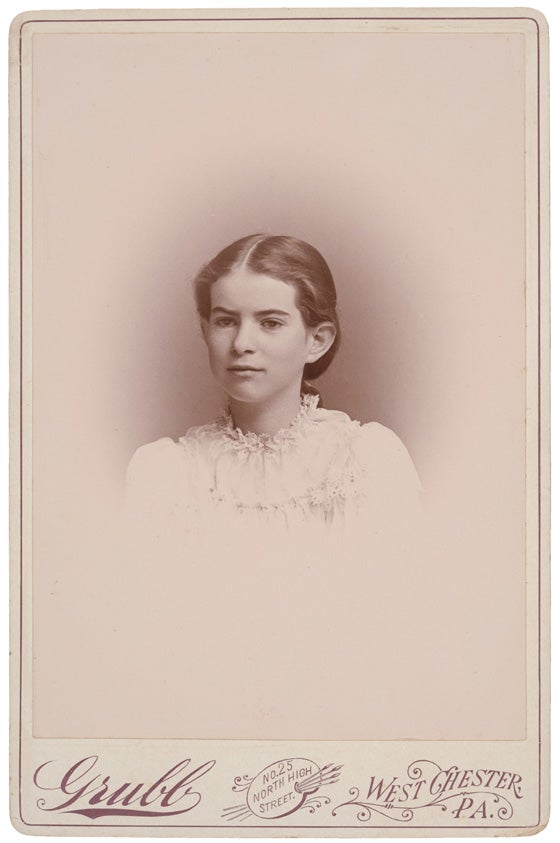

11

|

F. J. Nelson, Anoka and Lindstrom, Minnesota

Catch of Seth Owens, July 25, 1894

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

12

|

McLain, El Dorado, Kansas

Family meal, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

13

|

W. O. Towns, Lewistown, Pennsylvania

Boy in wheelchair, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

14

|

H. L. Austin, Berlin, New York

Family dog, late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

It was not unusual for people to commission portraits of their pets, but the dog in this image appears particularly pampered: sprawled across a settee before a country lane backdrop, the pet seems to radiate a life of comfort, economic well-being, and leisure.

|

|

15

|

A. M. Nikodem, Chicago, Illinois

Cat, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

|

|

16

|

G. Mandeville, Lowville, New York

Man, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

17

|

Perry Daniel Werts, Iowa City, Iowa

Graduate, c. 1900

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Cabinet cards documented all stages of life, creating a linearity of existence that paved the way for twentieth-century snapshot albums. This woman’s pose reflects the rise of educational opportunities for women.

|

|

18

|

C. H. Wareham, Freeport, Illinois

Blind woman, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

19

|

T. J. Grigsen, Terre Haute, Indiana

Family, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Americans’ embrace of cabinet cards in the late nineteenth century coincided with an increasing idealization of home and childhood. This family has chosen to display their domestic harmony by photographing their children and dog.

|

|

20

|

George W. Parsons, Pawhuska, Oklahoma Territory

Ni Wala, c. 1890

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

21

|

Morris, Oxford, Nebraska

Man, c. 1900

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

22

|

Mills, Middletown, New York

Woman, c. 1890

Collodion silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

Though informality was widely accepted in photographic portraiture by 1890, sitters rarely smiled for the camera. This photographer may have used electric light to cut the exposure to a second or so, then coaxed this woman into presenting a relaxed demeanor.

|

|

23

|

Woodhead & Wood, Farmington, New Hampshire

Woman, c. 1885

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

24

|

Thomas Lenhart, Allentown, Pennsylvania

Wedding party, c. 1896

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

25

|

L. M. Melander & Brothers, Chicago, Illinois

Wedding portrait, c. 1890

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

26

|

J. Katdy, Pomona, California

Friends, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

27

|

D. D. Upson, Hampton, Iowa

Two women, 1880s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

28

|

F. J. Nelson, Anoka, Minnesota

Domestic Bread, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

29

|

O’Neil, New Bedford, Massachusetts

Postman, late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

30

|

J. S. Fonfara, Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts

Waitresses, c. 1890

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

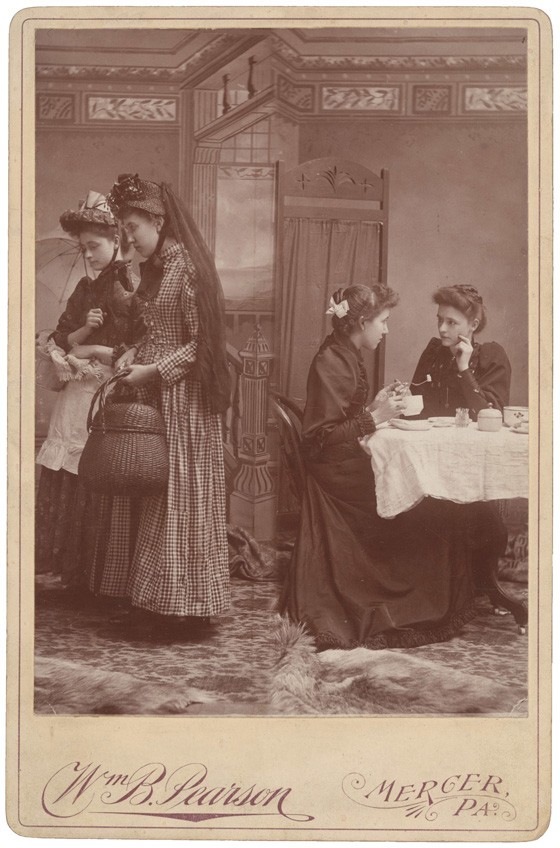

31

|

Frederick W. Jorns and William L. Harrod, Girard, Illinois

Family, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

James S. Jensen Collection

|

|

32

|

Baumann and Parker, Crawford, Nebraska

Barber and customer, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

In some images, it is difficult to tell if the sitter visited a studio to get a portrait made or the photographer carried his or her equipment out to the sitter’s home or workplace. This sitting may have been initiated by the barber, his customer, or both.

|

|

33

|

C. F. Voigt, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Carpenter, late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

|

|

34

|

E. W. Cook, Albany, New York

W. A. Forbes family store, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

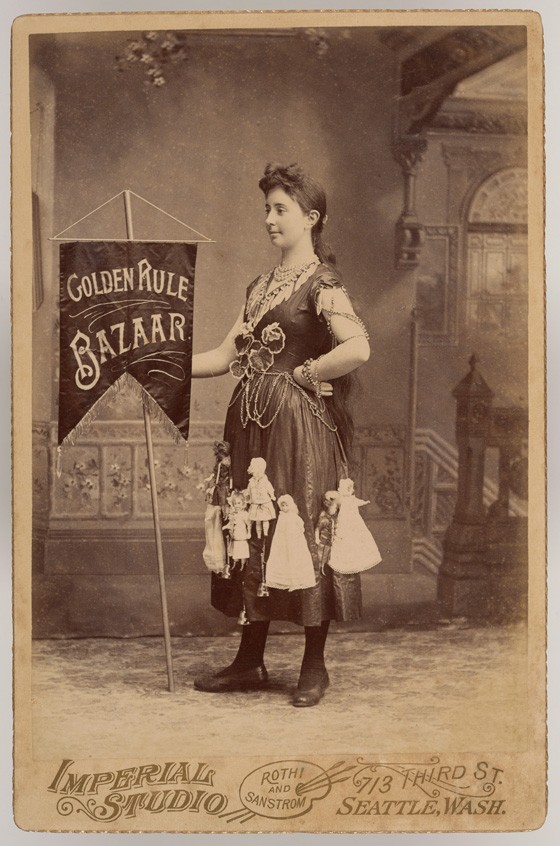

35

|

Harlan P. Goodman, Whitewater, Wisconsin

Banner lady for W. Grove, blacksmith, late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

|

|

36

|

J. Starr, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Doctors, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

37

|

Unknown photographer

Butchers, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

One would never know looking at cabinet cards that the 1890s was a decade filled with financial panics, strikes, and dislocations for Americans. Despite such uncertainties, individuals like these butchers took pride in their work and commemorated it in photographs.

|

|

38

|

Reed I. Case, Antigo, Wisconsin

Telegraph-line worker, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection, promised gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the museum’s 150th anniversary

|

|

39

|

H. A. Moore, Elma, Iowa

Telegrapher, 1890s

Albumen silver print

William L. Schaeffer Collection

|

|

40

|

Theodore E. Peiser, Seattle, Washington

Newspaper editor, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

|

|

41

|

W. F. Barnes, West Randolph, Vermont

Man with euphonium, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

42

|

Unknown photographer

Soldier, c. 1898

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

43

|

P. H. McAtee, Marshall, Missouri

Photographer with his chemicals, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

44

|

L. R. Phillips, Saguache, Colorado

George Norris, 1888

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

45

|

Houghton & Saxe, Plainview, Minnesota

Woman with photography album and journals, c. 1894

Collodion silver print

James S. Jensen Collection

|

|

46

|

Unknown photographer

Painter, 1890s

Albumen silver print

William L. Schaeffer Collection

|

|

47

|

Spencer Miller, Rochester, New York

Roller skater, mid-1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

In the mid-1880s, people began showing off their hobbies in cabinet cards, demonstrating how central photography had become to American life. It also indicates the rise of leisure time.

|

|

48

|

F. A. Place, Chicago, Illinois

Hats, 1910s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

49

|

John Albert Hawkins, Mansfield, Ohio

Lawnmower, c. 1890

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

50

|

Unknown photographer

Two boys with deer, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

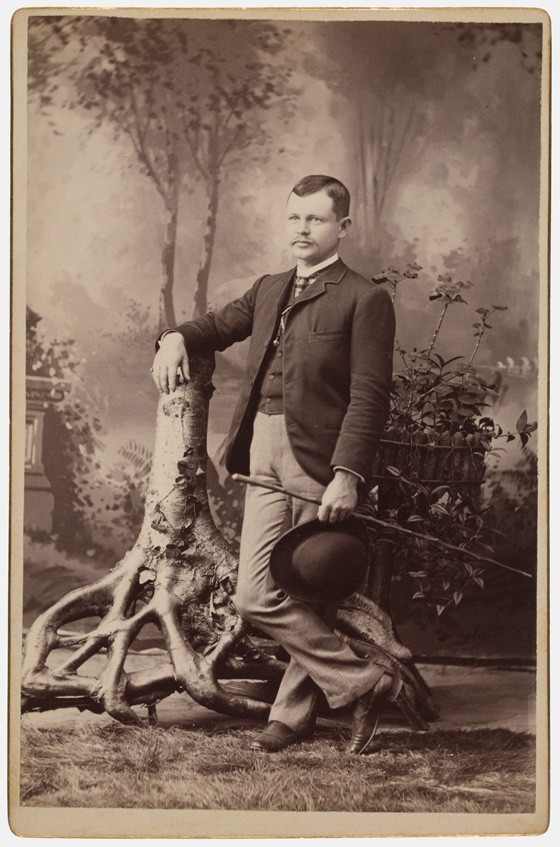

51

|

H. W. Calendar, Springfield, Ohio

Hunter, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

52

|

G. A. Werner, Marquette, Michigan

Sharing photos, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

53

|

W. R. Arnold, Watertown, Dakota Territory

The Renowned Gallagher Family, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

The sign, valises, and half-smiles in this image make it clear that these sitters are in total control of the photographic game. Their goal, besides making a family record, was to have fun.

|

|

54

|

Josiah Freeman, Nantucket, Massachusetts

Friends on an outing, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

55

|

O. F. Waegan, Burlington, Kansas

Sharing watermelon, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Cabinet cards were often sold by the dozen, encouraging people to commemorate even casual gatherings through the medium. Here, the photographer skillfully frames the messy activity of eating watermelon with a comfortable sense of order, gaiety, and even elegance.

|

|

56

|

Unknown photographer

Three men drinking beer, 1890s

Albumen silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art, William L. Schaeffer Collection, promised gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the museum’s 150th anniversary

|

|

57

|

Will Cundill, Maquoketa, Iowa

Sharing the paper, 1895

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

58

|

R. R. Carter, Basil, Ohio

Woman, early 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

59

|

F. A. Webster, Oakland, California

Woman in coffin, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

60

|

Ingalls, New Vineyard, Maine

Memorial portrait, 1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, gift of Robert E. Jackson

|

|

61

|

Frank E. Willis, Middletown, Connecticut

Deceased man, 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

62

|

J. M. Brigham, Plainwell, Michigan

Family, July 21, 1895

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

|

63

|

Atkinson

Family in parlor, 1890s

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

|

![Mrs. S. N. Likens, Police Matron from [Denver] Police Department, Christmas 1890, 1890](https://www-images.lacma.org/s3fs-public/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2021-08/P1981-10-63--70.jpg?itok=MEv7H-FX)