New galleries. More art. For all of Los Angeles.

A new way to encounter the world’s cultures—past, present, and future.

Over the last two decades, LACMA has sought to find new ways to embrace all the communities of Los Angeles County and honor all the world’s artistic traditions. Our goal is to make the experience of our collection richer and more accessible than ever before, while ensuring that the museum can be a place of reflection, expression, and empathy for everyone.

These years of evolution and expansion are culminating with the addition of the David Geffen Galleries, a magnificent new building for the permanent collection designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Peter Zumthor. With the $750 million goal met and exceeded as of August 2023, and construction well underway, we are in the final stages of bringing this next evolution of LACMA to all of Los Angeles.

Leading up to the construction of the David Geffen Galleries, the museum added two buildings, the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (2008) and the Resnick Exhibition Pavilion (2010), designed by another Pritzker Prize winner, Renzo Piano; enhanced outdoor programming with the installation of Urban Light (2008) and Levitated Mass (2012); and opened Ray’s and Stark Bar on our Smidt Welcome Plaza. We have also recently completed a major retrofit and renovation of a third building, the Pavilion for Japanese Art.

LACMA belongs to the people of Los Angeles County—this plan represents a fresh, Los Angeles take on a big art museum, one that is rooted in our commitment to openness, accessibility, and equity.

We invite you to be a part of the new LACMA.

New galleries. More art. For all of Los Angeles.

A new way to encounter the world’s cultures—past, present, and future.

Over the last two decades, LACMA has sought to find new ways to embrace all the communities of Los Angeles County and honor all the world’s artistic traditions. Our goal is to make the experience of our collection richer and more accessible than ever before, while ensuring that the museum can be a place of reflection, expression, and empathy for everyone.

These years of evolution and expansion are culminating with the addition of the David Geffen Galleries, a magnificent new building for the permanent collection designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Peter Zumthor. With the $750 million goal met and exceeded as of August 2023, and construction well underway, we are in the final stages of bringing this next evolution of LACMA to all of Los Angeles.

Leading up to the construction of the David Geffen Galleries, the museum added two buildings, the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (2008) and the Resnick Exhibition Pavilion (2010), designed by another Pritzker Prize winner, Renzo Piano; enhanced outdoor programming with the installation of Urban Light (2008) and Levitated Mass (2012); and opened Ray’s and Stark Bar on our Smidt Welcome Plaza. We have also recently completed a major retrofit and renovation of a third building, the Pavilion for Japanese Art.

LACMA belongs to the people of Los Angeles County—this plan represents a fresh, Los Angeles take on a big art museum, one that is rooted in our commitment to openness, accessibility, and equity.

We invite you to be a part of the new LACMA.

Renderings

How will areas of LACMA’s collection come to life as never before in the new David Geffen Galleries at LACMA? Find out in a series of short videos about the new building coming to our campus.

How will areas of LACMA’s collection come to life as never before in the new David Geffen Galleries at LACMA? Find out in a series of short videos about the new building coming to our campus.

The history of art is long, but the history of museums is short. The art museum as we know it has existed for less than three hundred years, a cabinet of far-flung curiosities first created for societies not yet familiar with the airplane, the television, or the internet. So much has changed in the world; the art museum must evolve as well.

Peter Zumthor’s plan for the new building to house LACMA’s galleries offers an alternative to the traditional museum model. His design is grounded in his commitment to creating “emotional space,” which mirrors LACMA’s own mission to cultivate meaningful connections between art and the people appreciating it.

Glass walls invite museum visitors to look out at the landscape and light of Los Angeles, and allow passersby to see in. This translucent exterior visually connects the galleries to everyday life on Wilshire Boulevard and in the surrounding park, and offers spectacular views of the city and mountains beyond. Zumthor’s design also adds ample new public outdoor space to create an even more accessible cultural and social hub for the community.

The horizontality of the new building is both a reflection of Los Angeles and a core concept within LACMA’s vision for presenting the permanent collection. It positions art from all areas of the museum’s diverse collections on the same plane, to better accommodate the shift in LACMA’s curatorial strategy from fixed presentations to rotating exhibitions of the permanent collection. The building is designed to mirror the diversity of our vast city and, through design and spirit, to advance LACMA’s mission to serve the public by encouraging profound cultural experiences for the widest array of audiences.

In order to build on the success and legacy of LACMA’s more than 50 years, the museum must lay a strong foundation for the future now. With extraordinary support from the County of Los Angeles and the board of trustees, as well as leadership gifts from David Geffen—whose historic gift is recognized in the building’s name, the David Geffen Galleries—and a number of other donors, fundraising for the project has been extremely successful and only continues to exceed expectations.

This success means the museum stands poised to complete the next step in its transformation, creating a landmark that will identify LACMA for its next 50 years and beyond.

Michael Govan

CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director

The history of art is long, but the history of museums is short. The art museum as we know it has existed for less than three hundred years, a cabinet of far-flung curiosities first created for societies not yet familiar with the airplane, the television, or the internet. So much has changed in the world; the art museum must evolve as well.

Peter Zumthor’s plan for the new building to house LACMA’s galleries offers an alternative to the traditional museum model. His design is grounded in his commitment to creating “emotional space,” which mirrors LACMA’s own mission to cultivate meaningful connections between art and the people appreciating it.

Glass walls invite museum visitors to look out at the landscape and light of Los Angeles, and allow passersby to see in. This translucent exterior visually connects the galleries to everyday life on Wilshire Boulevard and in the surrounding park, and offers spectacular views of the city and mountains beyond. Zumthor’s design also adds ample new public outdoor space to create an even more accessible cultural and social hub for the community.

The horizontality of the new building is both a reflection of Los Angeles and a core concept within LACMA’s vision for presenting the permanent collection. It positions art from all areas of the museum’s diverse collections on the same plane, to better accommodate the shift in LACMA’s curatorial strategy from fixed presentations to rotating exhibitions of the permanent collection. The building is designed to mirror the diversity of our vast city and, through design and spirit, to advance LACMA’s mission to serve the public by encouraging profound cultural experiences for the widest array of audiences.

In order to build on the success and legacy of LACMA’s more than 50 years, the museum must lay a strong foundation for the future now. With extraordinary support from the County of Los Angeles and the board of trustees, as well as leadership gifts from David Geffen—whose historic gift is recognized in the building’s name, the David Geffen Galleries—and a number of other donors, fundraising for the project has been extremely successful and only continues to exceed expectations.

This success means the museum stands poised to complete the next step in its transformation, creating a landmark that will identify LACMA for its next 50 years and beyond.

Michael Govan

CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director

To those whose immense generosity to the Building LACMA and Transformation campaigns is recognized below, thank you. Together, you have contributed over $1 billion since 2004 toward creating a future for LACMA for all of Los Angeles to enjoy.

Campaign Donors, $1 Million and Above

|

$100,000,000 and above County of Los Angeles |

$50,000,000 and above Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation

|

|

$25,000,000 and above A. Jerrold Perenchio

|

$20,000,000 and above Annenberg Foundation

|

|

$10,000,000 and above Debbie and Mark Attanasio |

$5,000,000 and above The Honorable Frank E. Baxter and Kathrine Baxter

|

|

$2,000,000 and above The Ahmanson Foundation

|

Elise Mudd Marvin Trust |

|

$1,000,000 and above The Honorable Nicole Avant and Ted Sarandos |

Robert and Mary M. Looker |

To those whose immense generosity to the Building LACMA and Transformation campaigns is recognized below, thank you. Together, you have contributed over $1 billion since 2004 toward creating a future for LACMA for all of Los Angeles to enjoy.

Campaign Donors, $1 Million and Above

|

$100,000,000 and above County of Los Angeles |

$50,000,000 and above Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation

|

|

$25,000,000 and above A. Jerrold Perenchio

|

$20,000,000 and above Annenberg Foundation

|

|

$10,000,000 and above Debbie and Mark Attanasio |

$5,000,000 and above The Honorable Frank E. Baxter and Kathrine Baxter

|

|

$2,000,000 and above The Ahmanson Foundation

|

Elise Mudd Marvin Trust |

|

$1,000,000 and above The Honorable Nicole Avant and Ted Sarandos |

Robert and Mary M. Looker |

An exciting aspect of LACMA’s new building is that it is Peter Zumthor’s first project in the United States. One of the world’s most respected architects, Zumthor is known for projects including the Therme Vals, Switzerland (1996); the Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (1997); Kolumba Art Museum, Cologne (2007); and the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, London (2011).

A hallmark of Zumthor’s work is that no two buildings are the same; it is often noted that he has no single style. Several characteristics, however, are common to each project. First is the attention to the site, and another is the use of specific materials—wood, concrete, brick, or stone. Most prized of all is Zumthor’s skillful choreography of light and shadow in each of his buildings.

Zumthor was trained as a cabinetmaker in his father’s shop in his native Basel, Switzerland, and subsequently attended Basel’s Kunstgewerbeschule (Arts and Crafts School) and Pratt Institute in New York City, where he studied industrial design and architecture. He began his career as a conservation architect for the Department for the Preservation of Monuments in the Swiss canton of Graubünden, an experience that deepened his knowledge of a wide range of construction methods and materials. He established his own architectural firm in 1978 in Haldenstein, Switzerland.

Before he began his work for LACMA in 2009, Zumthor taught in Los Angeles as a visiting professor at the University of Southern California and SCI-ARC. He has received international awards including the Praemium Imperiale, the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and the Pritzker Architecture Prize—the most prestigious recognition in the field—for his distinguished body of work

An exciting aspect of LACMA’s new building is that it is Peter Zumthor’s first project in the United States. One of the world’s most respected architects, Zumthor is known for projects including the Therme Vals, Switzerland (1996); the Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (1997); Kolumba Art Museum, Cologne (2007); and the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, London (2011).

A hallmark of Zumthor’s work is that no two buildings are the same; it is often noted that he has no single style. Several characteristics, however, are common to each project. First is the attention to the site, and another is the use of specific materials—wood, concrete, brick, or stone. Most prized of all is Zumthor’s skillful choreography of light and shadow in each of his buildings.

Zumthor was trained as a cabinetmaker in his father’s shop in his native Basel, Switzerland, and subsequently attended Basel’s Kunstgewerbeschule (Arts and Crafts School) and Pratt Institute in New York City, where he studied industrial design and architecture. He began his career as a conservation architect for the Department for the Preservation of Monuments in the Swiss canton of Graubünden, an experience that deepened his knowledge of a wide range of construction methods and materials. He established his own architectural firm in 1978 in Haldenstein, Switzerland.

Before he began his work for LACMA in 2009, Zumthor taught in Los Angeles as a visiting professor at the University of Southern California and SCI-ARC. He has received international awards including the Praemium Imperiale, the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and the Pritzker Architecture Prize—the most prestigious recognition in the field—for his distinguished body of work

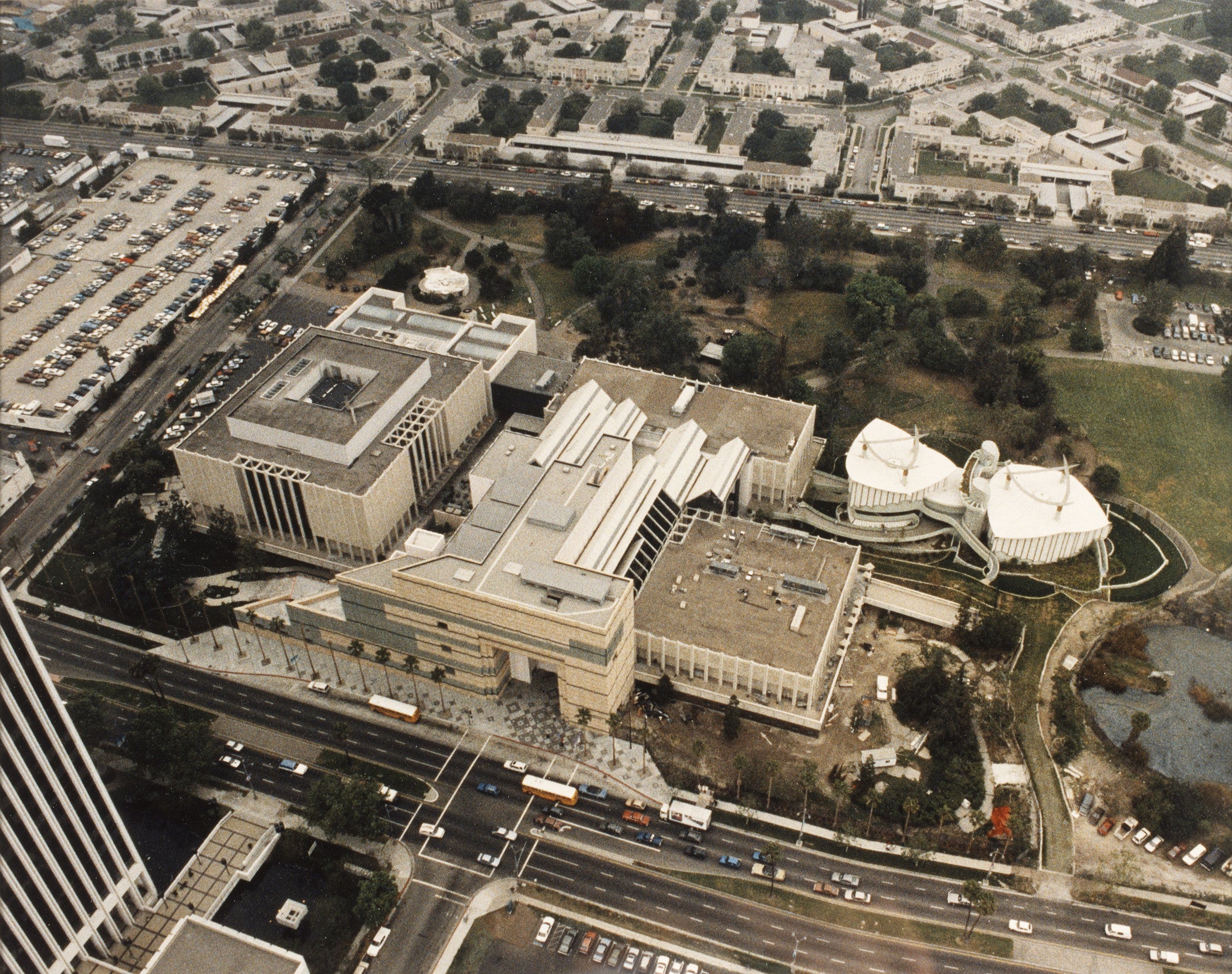

With construction of the David Geffen Galleries well underway, we have surpassed the midway point of LACMA's current transformation. The history below details how LACMA’s campus has been imagined, built, and rebuilt since before it opened on Wilshire Boulevard in 1965.

An Art Collection Begins

Frank Dale Hudson and William A. O. Munsell, architects

The Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art in Exposition Park was completed in 1913 in the French beaux-arts style emblematic of high culture in the early twentieth century. In the late 1950s, museum and other civic leaders—in response to the rapidly expanding collection and the conviction that a hallmark of a major city was an independent art museum—initiated a movement to establish a dedicated building for art. The County Museum was divided into two separate institutions in 1961, with what is now the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County remaining in the original location.

Choosing a Site and an Architect

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Museum Archives

The site chosen for the new art museum was the La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park. One of the world’s richest and most renowned sources of late Ice Age fossils, it had become a public park in 1924. After the county approved a separate building for an art museum, an intensive search for the right architect began. LACMA’s ambitious and adventurous chief curator of art, Richard “Ric” Brown, who would become director in 1961, was a passionate advocate of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. While Brown asserted that Mies was “considered to be the greatest living architect,” he presented other choices to the board, whose members had their own preferences. Local architect William L. Pereira was a compromise candidate and his firm was given the commission in March 1960. As Edward Carter, the board chair, told the Los Angeles Times in a 1979 interview: “We all decided Pereira would be a satisfactory second choice.”

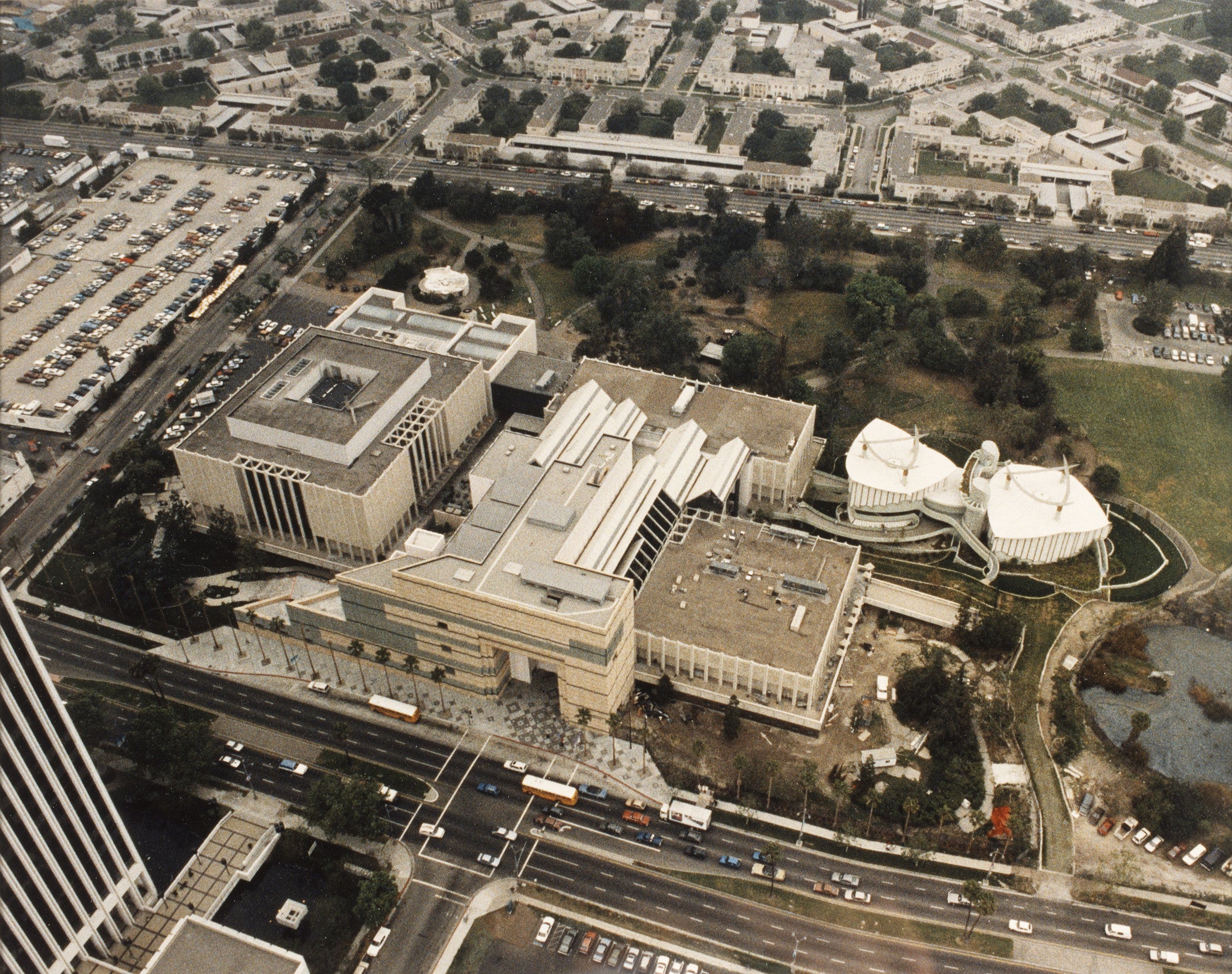

The William L. Pereira Buildings

William L. Pereira, architect; Thomas Dolliver Church, landscape architect; Robert Herrick Carter, landscape architect

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art opened in March 1965, amid an outpouring of civic pride and a spectacle of fireworks. Designed in a modern classicist style, the new museum consisted of three pavilions: the Ahmanson Gallery of Art, which housed the permanent collections; the Lytton Gallery, for temporary exhibitions; and the Leo S. Bing Center, which included the theater, library, and education spaces.

William L. Pereira, architect; photo: Ralph Crane/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Many admired the new art acropolis and how it appeared to float over the biomorphic pools and fountains. While the Los Angeles Times heralded it as a “noble contribution to the world of art,” assessments of the buildings were always mixed. The decision to have multiple structures had been political—the board adhered to the wishes of the largest donors. This created immediate circulation issues and, almost from the very beginning, the galleries were considered to be confusingly laid out and too small. The reflecting pools were central to Pereira’s plan and their almost immediate failure greatly compromised his intent. His firm had taken some measures to mitigate seepage from Hancock Park’s viscous soil, but the board of trustees noted the “highly inflammable gas” in the east pool and the need to constantly drain all the water features just 18 months after opening. The seepage of black tar remained a serious issue; within 10 years, the pools were drained and replaced with a sculpture garden.

William L. Pereira, architect; photo: Ralph Crane/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

At the core of the Ahmanson Gallery was a skylighted atrium intended to display large works of art and provide a space for parties and important events. The museum’s second director, Kenneth Donahue, spoke for many who objected that this expansive hall had attained its size at the expense of the surrounding galleries. In order to cut costs, the galleries had been made narrower than originally planned. Critics complained that these spaces, which overlooked the atrium from a border of balconies, were too shallow and difficult to navigate. Over time, the open walls were filled in with large panels, which increased the space available for displaying art but dramatically altered the original building design. Present-day building code requirements prevented the restoration of the original intent for the spaces.

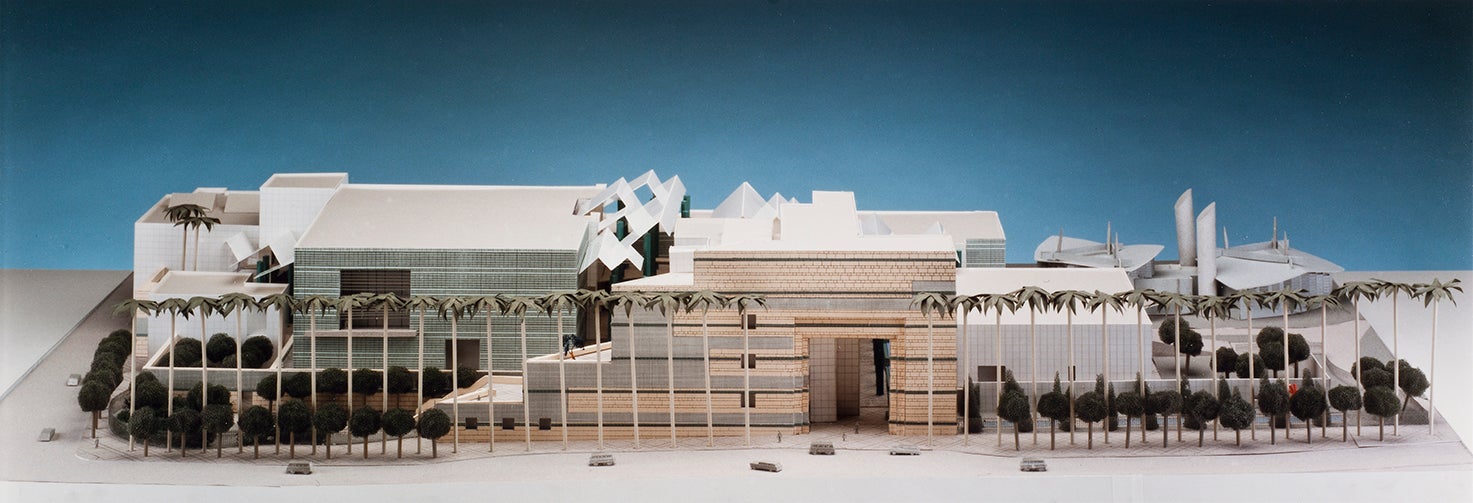

An Addition by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer

Hugh Hardy; Malcolm Holzman and Norman Pfeiffer, Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates

By the 1980s the collection had drastically outgrown its footprint, and LACMA’s director, Earl A. “Rusty” Powell III, led an effort to expand the institution. Both the director and the trustees clearly recognized the need for a building dedicated to 20th-century art. The Robert O. Anderson Building (completed in 1986 and renamed the Art of the Americas Building) was designed by the New York firm Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates. In an effort to resolve the frustrating circulation patterns that had plagued the original design, the architects joined the existing buildings with a central courtyard and reoriented the museum toward Wilshire Boulevard with an oversize facade referencing the art moderne style of classic Hollywood.

Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer had other plans to unify the campus. They proposed recladding the original 1965 buildings with green terracotta tile and porcelain panels to match the new construction as well as joining the buildings with pedestrian walkways at all corresponding levels. Part of this master plan was enacted, but Powell’s departure in 1992 ensured that it would never be completed. And although the galleries, laid out in a traditional beaux-arts enfilade, were praised, the new building was seen as contributing to the aesthetic discord. The critic Robert Hughes’s comment that the Anderson Building “obliterated the old museum like the giant foot in Monty Python” was typical.

Bruce Goff’s Pavilion

Bruce Goff with Bart Prince, architects

A disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright and an advocate of organic architecture, the Oklahoma-based architect Bruce Goff was known for working closely with his patrons. While Joe Price was the original commissioner of the Pavilion for Japanese Art (completed in 1988), he declared, “We . . . designated a new type of client—the art itself.” Designed to house Price’s world-class collection of Edo period scroll and screen paintings, the gallery space evoked the way the works would have been displayed in traditional Japanese homes. A multistory spiral ramp led visitors on a defined path through the gallery, punctuated by horizontal viewing platforms. Instead of grouping paintings on walls, Goff created alcoves reminiscent of traditional Japanese tokonoma that promote intimate encounters with each artwork. The suspended roof enabled the paneled walls to be made of Kalwall, a translucent plastic meant, as Goff’s architectural collaborator Bart Prince explained, “to allow the natural light to filter through in a similar fashion as shoji screens” and also provided a more integrated relationship to the surrounding park.

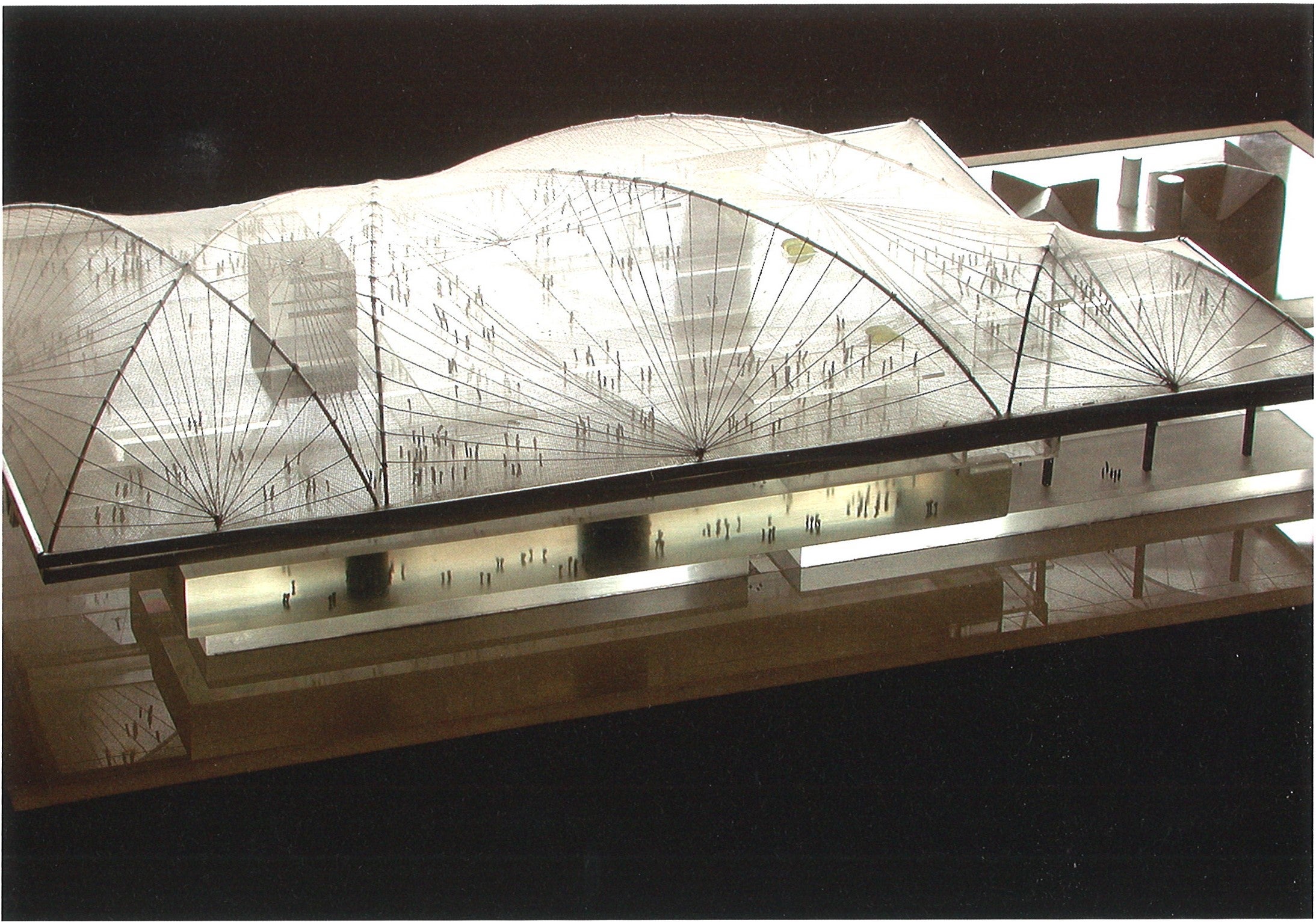

Rem Koolhaas’s Proposal

Rem Koolhaas, OMA (Office of Metropolitan Architecture)

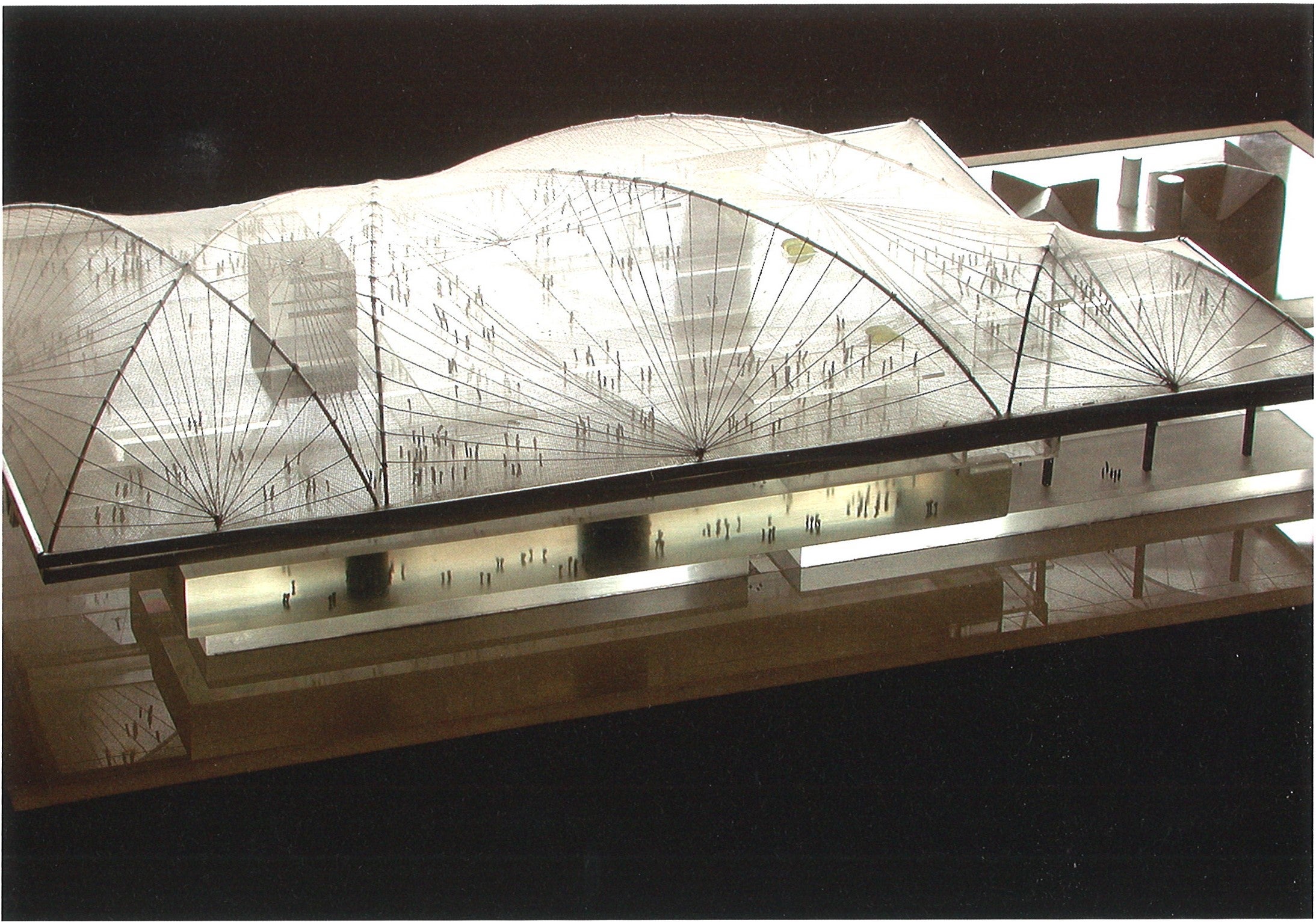

In 2001 LACMA’s board of trustees and the museum’s director, Andrea Rich, organized a competition, commissioning five internationally recognized architects to address what the museum admitted was “a disconnected and disorienting” campus experience. While four of the finalists adhered to the brief of renovation and an addition to the existing structures, the iconoclastic Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas galvanized the committee with his radical proposal to demolish most of the existing campus. In its place, he planned to erect a holistic museum under a single undulating Mylar-fiber roof. He hoped that his plan to elevate the structure over an expanded plaza on a series of concrete columns would finally integrate the site by allowing people to move freely between building, park, and city. Although this winning plan failed to garner the necessary financial support, Koolhaas’s assertion that much of the east campus should not be preserved was a lasting legacy, as was his determination to display all of the collections on a single level. Given the great cost of seismic retrofitting and the logistical and aesthetic deficiencies of the buildings, his plan convinced many that LACMA’s best course would be to start anew. Recent assessments have estimated the necessary repairs at more than $300 million, affirming the prescience of Koolhaas’s intuition.

Rem Koolhaas, OMA (Office of Metropolitan Architecture)

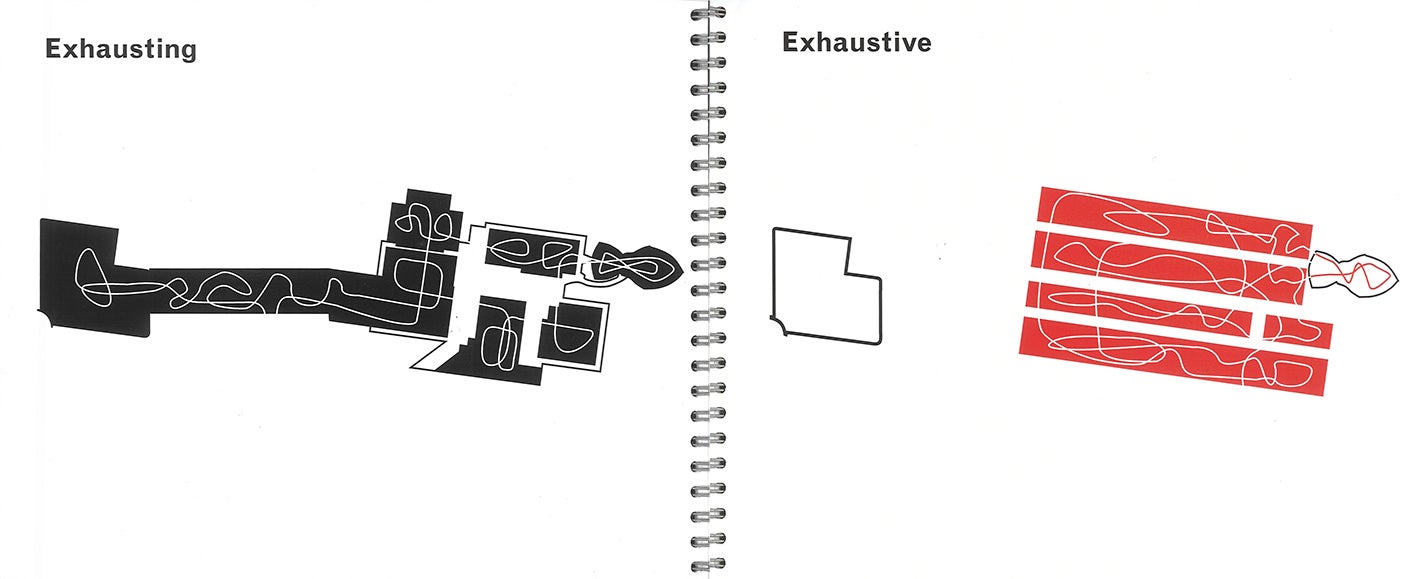

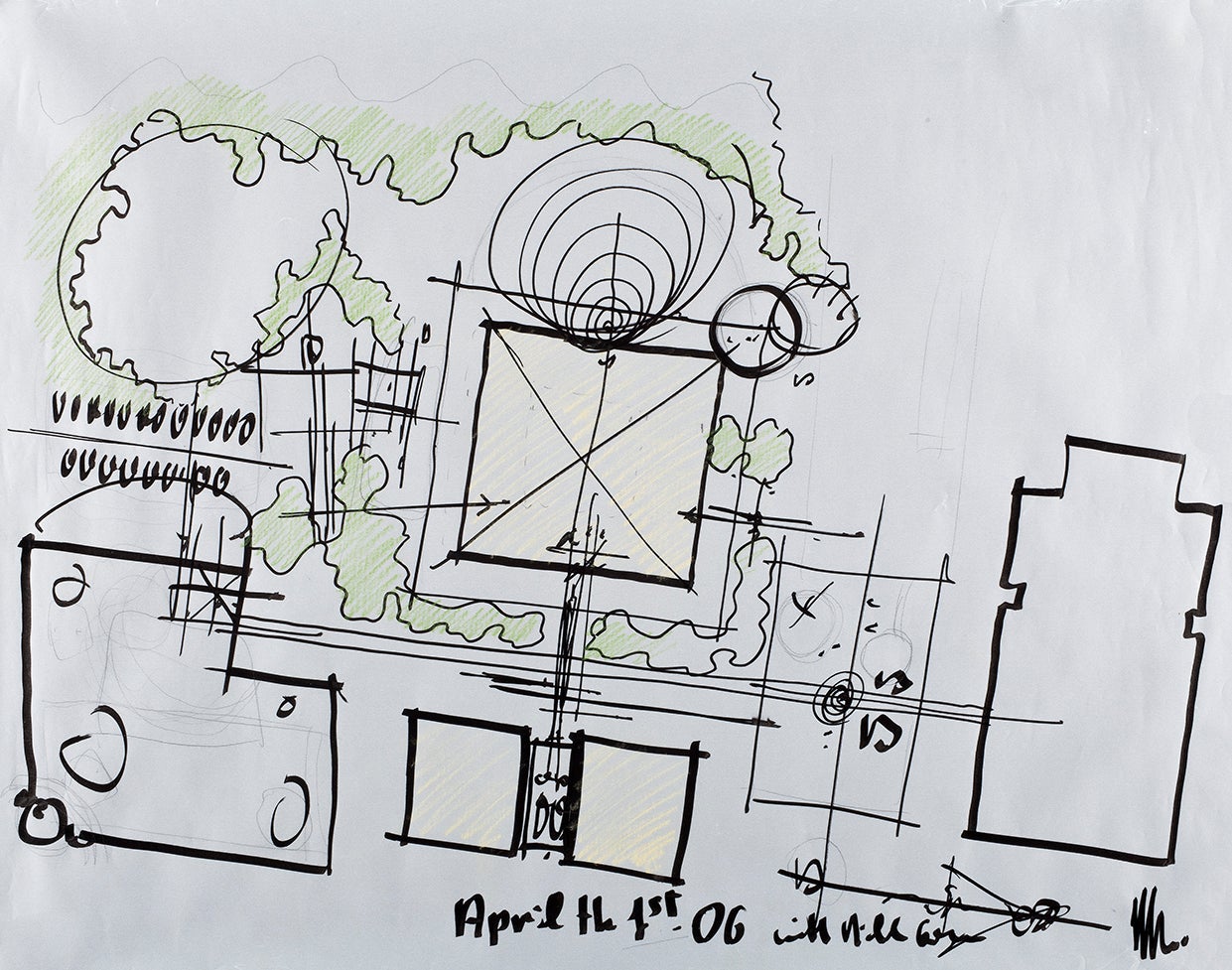

Renzo Piano’s Plan

Renzo Piano, architect

After economic issues prevented the implementation of Koolhaas’s plan, LACMA’s board of trustees sought an alternative resolution to the museum’s architectural challenges. Trustee Eli Broad, with the support of the other board members, originally approached the Italian architect Renzo Piano to design a single freestanding building that would be called the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM). Piano accepted the commission under the condition that his firm would “redo everything on the LACMA campus,” stating, “We have to find a solution for the whole thing.”

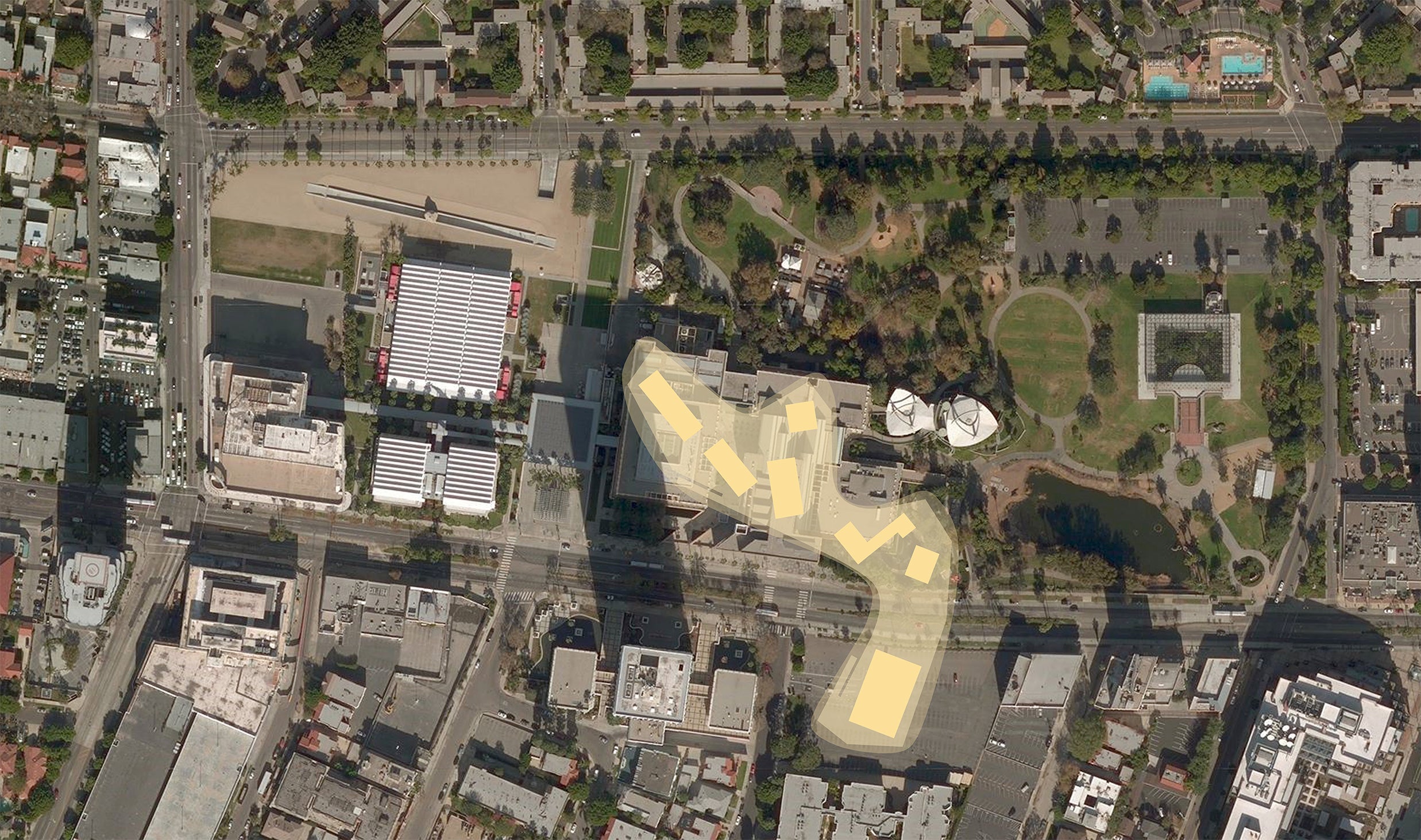

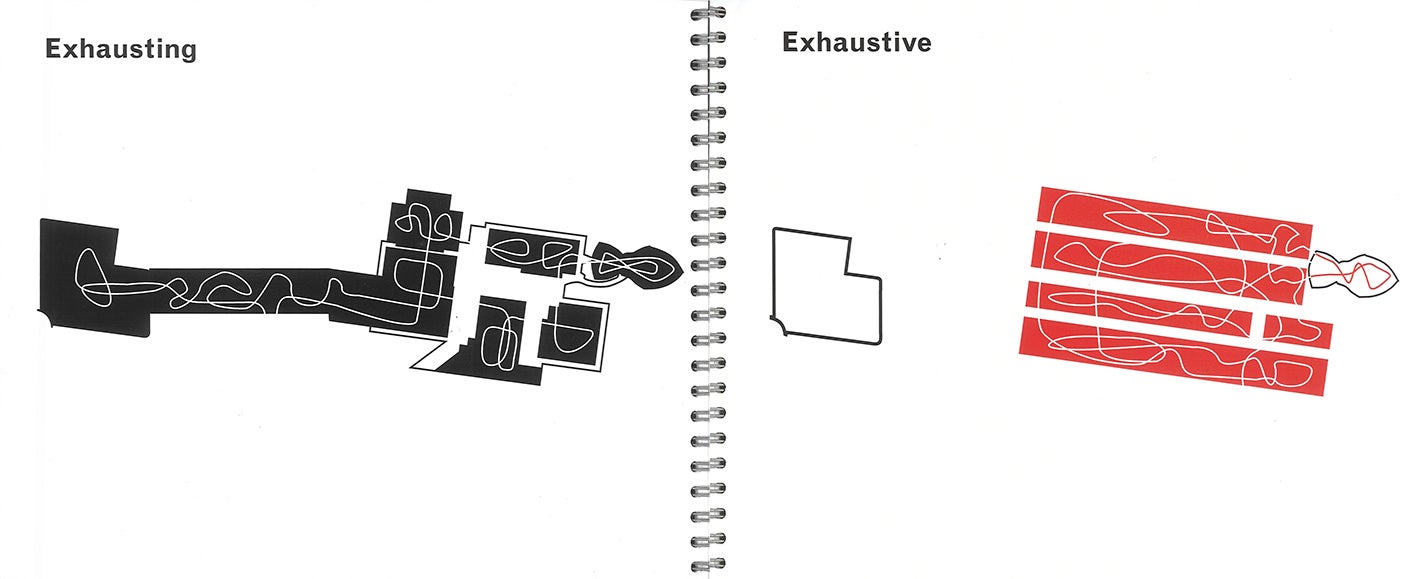

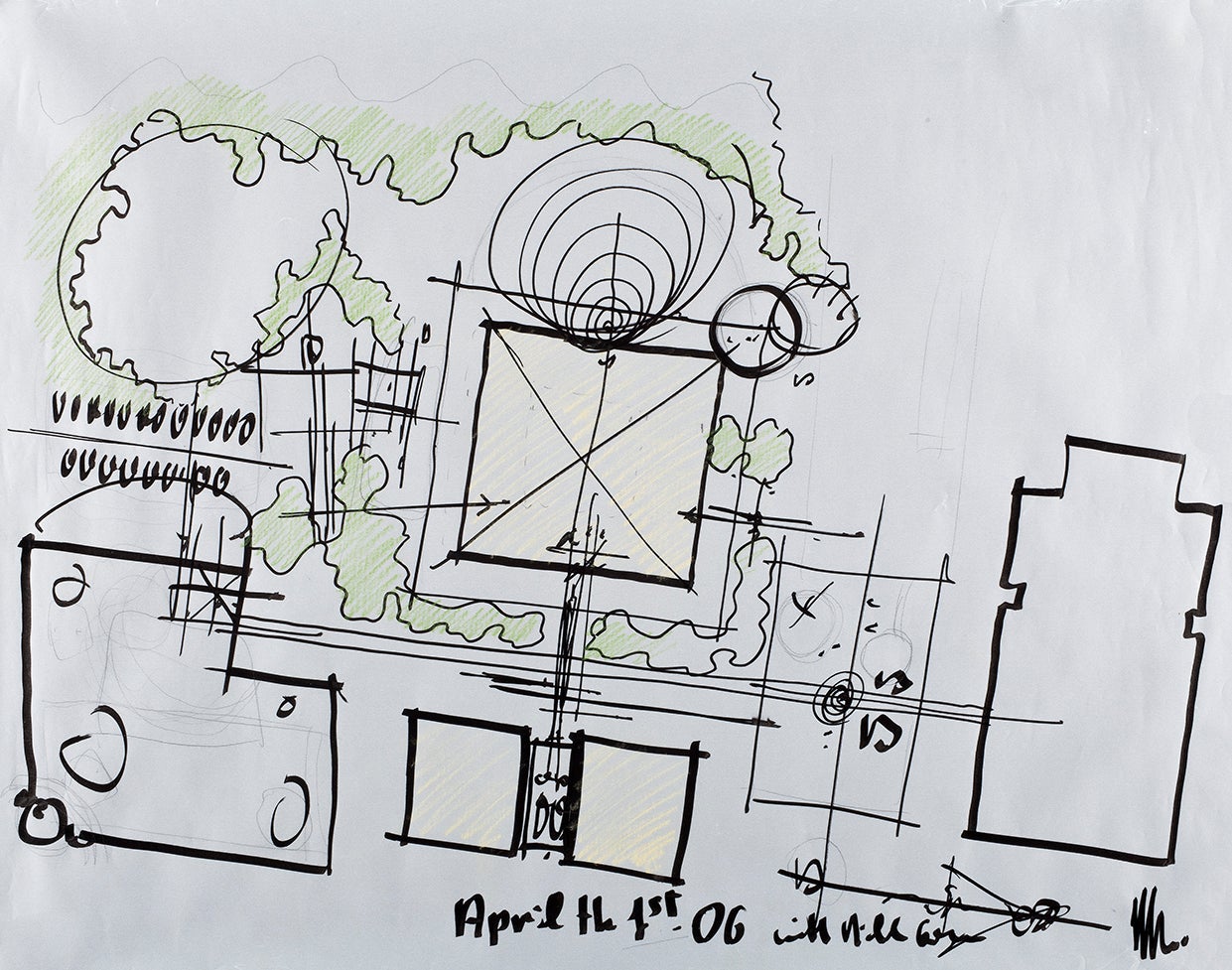

Piano’s master plan proposed clarifying the museum’s notoriously flawed circulation pattern with a classical axis system of two pedestrian paths. What he called the “sacred” axis led visitors between the art galleries, flowing from LACMA West alongside the new structure (BCAM would be completed in 2008), through the Ahmanson Building (which would be reconfigured to permit visitors to walk east and west), up to the central courtyard and, ideally, past the Tar Pits. Arguing that the “park is part of the experience,” Piano saw the entire campus as encompassing both artistic and scientific discovery. A perpendicular “profane” axis connected the shop and restaurant, moving people through a light-filled entry pavilion to an outdoor plaza. In 2006 Piano refined the plan with then-new director Michael Govan, converting the entry into an open-air space and ultimately designing a second building, the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Exhibition Pavilion, which opened in 2010. Between BCAM and the Resnick Pavilion, the museum gained 100,000 square feet for the display of art, effectively doubling LACMA’s gallery spaces and ensuring the continuation of vibrant exhibition programming during the anticipated rebuild of the east campus.

Peter Zumthor’s Vision

From William L. Pereira’s original scheme of the early 1960s and Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer’s attempted solutions in the ’80s, to Rem Koolhaas’s groundbreaking proposals of 2001 and Renzo Piano’s vision of unity outlined in 2006, the history of LACMA’s campus is a study of how financial restrictions, political compromises, and unrealized plans have impacted the museum’s architecture and the public’s art-viewing experience.

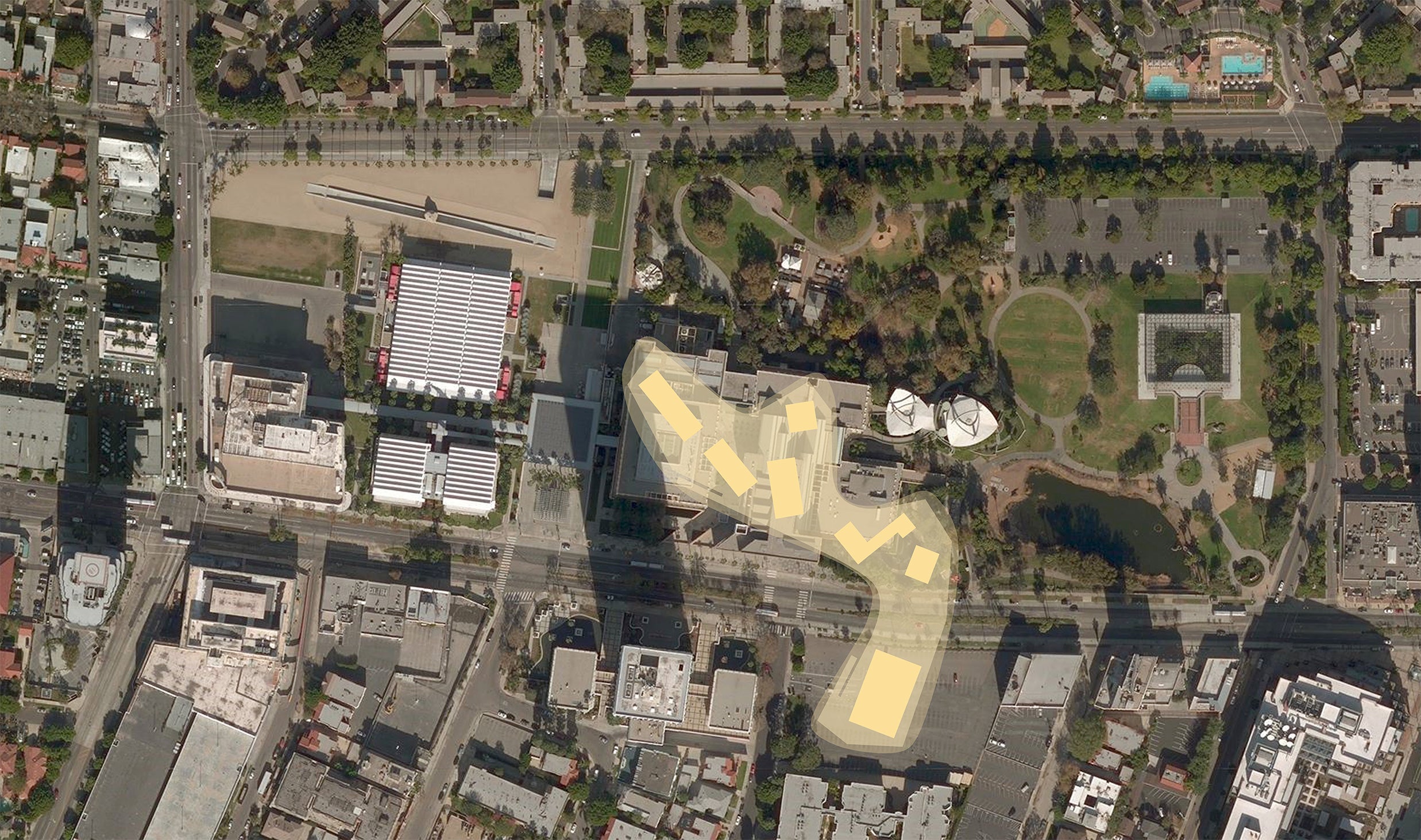

Peter Zumthor’s plans for the David Geffen Galleries present an opportunity to counter this history. The design ensures a future for LACMA that better serves the people of Los Angeles by facilitating richer, more meaningful experiences with art, while also fulfilling the decades-long intent to architecturally and spatially unify the museum’s Wilshire campus, while at the same time creating more public park and open space.

With construction of the David Geffen Galleries well underway, we have surpassed the midway point of LACMA's current transformation. The history below details how LACMA’s campus has been imagined, built, and rebuilt since before it opened on Wilshire Boulevard in 1965.

An Art Collection Begins

Frank Dale Hudson and William A. O. Munsell, architects

The Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art in Exposition Park was completed in 1913 in the French beaux-arts style emblematic of high culture in the early twentieth century. In the late 1950s, museum and other civic leaders—in response to the rapidly expanding collection and the conviction that a hallmark of a major city was an independent art museum—initiated a movement to establish a dedicated building for art. The County Museum was divided into two separate institutions in 1961, with what is now the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County remaining in the original location.

Choosing a Site and an Architect

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Museum Archives

The site chosen for the new art museum was the La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park. One of the world’s richest and most renowned sources of late Ice Age fossils, it had become a public park in 1924. After the county approved a separate building for an art museum, an intensive search for the right architect began. LACMA’s ambitious and adventurous chief curator of art, Richard “Ric” Brown, who would become director in 1961, was a passionate advocate of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. While Brown asserted that Mies was “considered to be the greatest living architect,” he presented other choices to the board, whose members had their own preferences. Local architect William L. Pereira was a compromise candidate and his firm was given the commission in March 1960. As Edward Carter, the board chair, told the Los Angeles Times in a 1979 interview: “We all decided Pereira would be a satisfactory second choice.”

The William L. Pereira Buildings

William L. Pereira, architect; Thomas Dolliver Church, landscape architect; Robert Herrick Carter, landscape architect

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art opened in March 1965, amid an outpouring of civic pride and a spectacle of fireworks. Designed in a modern classicist style, the new museum consisted of three pavilions: the Ahmanson Gallery of Art, which housed the permanent collections; the Lytton Gallery, for temporary exhibitions; and the Leo S. Bing Center, which included the theater, library, and education spaces.

William L. Pereira, architect; photo: Ralph Crane/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Many admired the new art acropolis and how it appeared to float over the biomorphic pools and fountains. While the Los Angeles Times heralded it as a “noble contribution to the world of art,” assessments of the buildings were always mixed. The decision to have multiple structures had been political—the board adhered to the wishes of the largest donors. This created immediate circulation issues and, almost from the very beginning, the galleries were considered to be confusingly laid out and too small. The reflecting pools were central to Pereira’s plan and their almost immediate failure greatly compromised his intent. His firm had taken some measures to mitigate seepage from Hancock Park’s viscous soil, but the board of trustees noted the “highly inflammable gas” in the east pool and the need to constantly drain all the water features just 18 months after opening. The seepage of black tar remained a serious issue; within 10 years, the pools were drained and replaced with a sculpture garden.

William L. Pereira, architect; photo: Ralph Crane/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

At the core of the Ahmanson Gallery was a skylighted atrium intended to display large works of art and provide a space for parties and important events. The museum’s second director, Kenneth Donahue, spoke for many who objected that this expansive hall had attained its size at the expense of the surrounding galleries. In order to cut costs, the galleries had been made narrower than originally planned. Critics complained that these spaces, which overlooked the atrium from a border of balconies, were too shallow and difficult to navigate. Over time, the open walls were filled in with large panels, which increased the space available for displaying art but dramatically altered the original building design. Present-day building code requirements prevented the restoration of the original intent for the spaces.

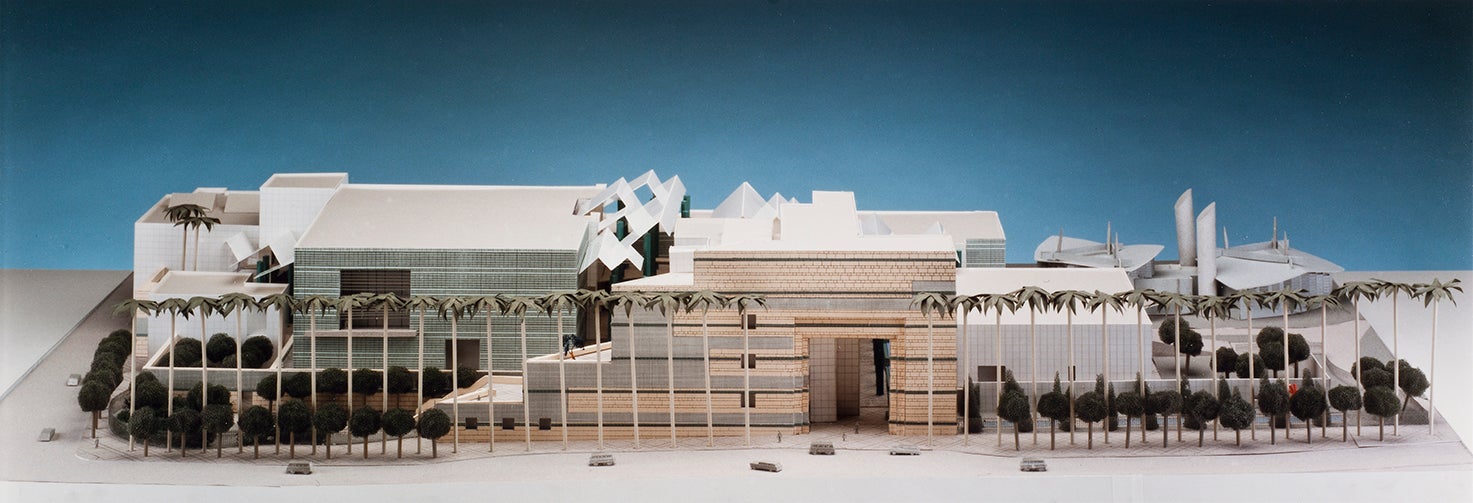

An Addition by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer

Hugh Hardy; Malcolm Holzman and Norman Pfeiffer, Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates

By the 1980s the collection had drastically outgrown its footprint, and LACMA’s director, Earl A. “Rusty” Powell III, led an effort to expand the institution. Both the director and the trustees clearly recognized the need for a building dedicated to 20th-century art. The Robert O. Anderson Building (completed in 1986 and renamed the Art of the Americas Building) was designed by the New York firm Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates. In an effort to resolve the frustrating circulation patterns that had plagued the original design, the architects joined the existing buildings with a central courtyard and reoriented the museum toward Wilshire Boulevard with an oversize facade referencing the art moderne style of classic Hollywood.

Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer had other plans to unify the campus. They proposed recladding the original 1965 buildings with green terracotta tile and porcelain panels to match the new construction as well as joining the buildings with pedestrian walkways at all corresponding levels. Part of this master plan was enacted, but Powell’s departure in 1992 ensured that it would never be completed. And although the galleries, laid out in a traditional beaux-arts enfilade, were praised, the new building was seen as contributing to the aesthetic discord. The critic Robert Hughes’s comment that the Anderson Building “obliterated the old museum like the giant foot in Monty Python” was typical.

Bruce Goff’s Pavilion

Bruce Goff with Bart Prince, architects

A disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright and an advocate of organic architecture, the Oklahoma-based architect Bruce Goff was known for working closely with his patrons. While Joe Price was the original commissioner of the Pavilion for Japanese Art (completed in 1988), he declared, “We . . . designated a new type of client—the art itself.” Designed to house Price’s world-class collection of Edo period scroll and screen paintings, the gallery space evoked the way the works would have been displayed in traditional Japanese homes. A multistory spiral ramp led visitors on a defined path through the gallery, punctuated by horizontal viewing platforms. Instead of grouping paintings on walls, Goff created alcoves reminiscent of traditional Japanese tokonoma that promote intimate encounters with each artwork. The suspended roof enabled the paneled walls to be made of Kalwall, a translucent plastic meant, as Goff’s architectural collaborator Bart Prince explained, “to allow the natural light to filter through in a similar fashion as shoji screens” and also provided a more integrated relationship to the surrounding park.

Rem Koolhaas’s Proposal

Rem Koolhaas, OMA (Office of Metropolitan Architecture)

In 2001 LACMA’s board of trustees and the museum’s director, Andrea Rich, organized a competition, commissioning five internationally recognized architects to address what the museum admitted was “a disconnected and disorienting” campus experience. While four of the finalists adhered to the brief of renovation and an addition to the existing structures, the iconoclastic Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas galvanized the committee with his radical proposal to demolish most of the existing campus. In its place, he planned to erect a holistic museum under a single undulating Mylar-fiber roof. He hoped that his plan to elevate the structure over an expanded plaza on a series of concrete columns would finally integrate the site by allowing people to move freely between building, park, and city. Although this winning plan failed to garner the necessary financial support, Koolhaas’s assertion that much of the east campus should not be preserved was a lasting legacy, as was his determination to display all of the collections on a single level. Given the great cost of seismic retrofitting and the logistical and aesthetic deficiencies of the buildings, his plan convinced many that LACMA’s best course would be to start anew. Recent assessments have estimated the necessary repairs at more than $300 million, affirming the prescience of Koolhaas’s intuition.

Rem Koolhaas, OMA (Office of Metropolitan Architecture)

Renzo Piano’s Plan

Renzo Piano, architect

After economic issues prevented the implementation of Koolhaas’s plan, LACMA’s board of trustees sought an alternative resolution to the museum’s architectural challenges. Trustee Eli Broad, with the support of the other board members, originally approached the Italian architect Renzo Piano to design a single freestanding building that would be called the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (BCAM). Piano accepted the commission under the condition that his firm would “redo everything on the LACMA campus,” stating, “We have to find a solution for the whole thing.”

Piano’s master plan proposed clarifying the museum’s notoriously flawed circulation pattern with a classical axis system of two pedestrian paths. What he called the “sacred” axis led visitors between the art galleries, flowing from LACMA West alongside the new structure (BCAM would be completed in 2008), through the Ahmanson Building (which would be reconfigured to permit visitors to walk east and west), up to the central courtyard and, ideally, past the Tar Pits. Arguing that the “park is part of the experience,” Piano saw the entire campus as encompassing both artistic and scientific discovery. A perpendicular “profane” axis connected the shop and restaurant, moving people through a light-filled entry pavilion to an outdoor plaza. In 2006 Piano refined the plan with then-new director Michael Govan, converting the entry into an open-air space and ultimately designing a second building, the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Exhibition Pavilion, which opened in 2010. Between BCAM and the Resnick Pavilion, the museum gained 100,000 square feet for the display of art, effectively doubling LACMA’s gallery spaces and ensuring the continuation of vibrant exhibition programming during the anticipated rebuild of the east campus.

Peter Zumthor’s Vision

From William L. Pereira’s original scheme of the early 1960s and Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer’s attempted solutions in the ’80s, to Rem Koolhaas’s groundbreaking proposals of 2001 and Renzo Piano’s vision of unity outlined in 2006, the history of LACMA’s campus is a study of how financial restrictions, political compromises, and unrealized plans have impacted the museum’s architecture and the public’s art-viewing experience.

Peter Zumthor’s plans for the David Geffen Galleries present an opportunity to counter this history. The design ensures a future for LACMA that better serves the people of Los Angeles by facilitating richer, more meaningful experiences with art, while also fulfilling the decades-long intent to architecturally and spatially unify the museum’s Wilshire campus, while at the same time creating more public park and open space.

What does the new building project entail?

The building project entails the construction of one modern and efficient building to replace four aging buildings (Ahmanson, Art of the Americas, Bing, Hammer), as well as the construction of a parking structure on Ogden Drive to replace the spaces on the previous Spaulding Avenue parking lot.

Why is LACMA replacing its old buildings?

The old buildings had many serious structural issues and problems with plumbing, sewage, lack of seismic isolation and methane mitigation, defunct waterproofing, and leaks, compromising their ability to host our visitors and staff and hold our collections.

Why couldn’t you repair the old buildings?

To retrofit the existing buildings would be extremely costly while still failing to provide the ideal setting for the collections and visitors. Almost 20 years ago, and again in 2014, the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors and LACMA’s Board of Trustees considered repairing the structures, and in both cases they found the retrofitting cost prohibitive. In 2014, the minimum estimated cost to retrofit just the visible deterioration was $246 million. New construction allows the museum to create both a safer building and new galleries designed to be more accessible, more functional, and more enjoyable.

Why are the galleries on one level?

The horizontal design offers an egalitarian experience of LACMA’s diverse collections. Displaying all art on a single level avoids giving more prominence to any specific culture, tradition, or era, offering visitors a multitude of perspectives on art and art history in a more accessible, inclusive way. The single-level gallery floor will also be more intuitive to navigate and easier to access, especially for wheelchairs and strollers, and its perimeter of transparent glass will provide energizing natural light and views to the park and urban environment, with views from outside into the galleries.

Why does the building cross Wilshire Boulevard?

The new building spans Wilshire in order to provide 3.5 acres of new park and outdoor space for visitors in Hancock Park and the Natural History Museum’s ongoing and future research. This public outdoor space will be home to even more public sculptures and is an invaluable resource in our dense urban community.

How big will the new building be?

The new building totals 347,500 square feet, replacing approximately 393,000 square feet of existing buildings. There will be approximately 110,000 square feet of gallery space, replacing approximately 120,000 square feet of gallery space. The building also includes a new theater, education spaces, three restaurant/cafes, a museum shop, and covered multipurpose event spaces. Much-improved ancillary and back-of-house facilities will support LACMA’s public programs, including two loading docks and enhanced security, facilities operations, visitor services, transit art handling, and more.

How did you reduce the size of the new building from the size of the existing buildings?

The reduction in total size from that of the existing buildings is made possible by moving functions not needed within the building itself: the museum has moved offices across the street, expanding our existing office space at 5900 Wilshire, and moved art storage out of Hancock Park.

How much will LACMA’s gallery space have increased in total once the new building is completed?

By the time the new building opens, we will have expanded our total gallery space from approximately 130,000 in 2007 to 220,000 square feet.

Does LACMA need more gallery space in its Wilshire campus?

LACMA’s Board of Trustees and the County Board of Supervisors believe that after doubling our exhibition space over the last decade, this is the appropriate size for our campus on Wilshire.

What is the budget for the new building?

Of the $750 million campaign goal, the total building budget is $650 million, which includes construction costs, soft costs, and contingencies. Of the $650 million, the construction costs (“hard costs”) are estimated at $490 million. A rigorous cost estimating and cost management process was followed throughout the preconstruction phase to be within budget and a guaranteed maximum price contract was signed with our general contractor, Clark Construction, in mid-2020, in line with our budget. The construction cost is in line with similar projects and the cost per square foot of LACMA's Renzo Piano–designed gallery buildings, BCAM and Resnick Pavilion (adjusted for inflation).

How is this new building being funded?

This building cost is funded through an unprecedented public-private partnership by which the new County-owned building will be 80% paid for by private donations. The County of Los Angeles has contributed $125 million and the rest came from private donations. The County will receive a 4:1 match for its contribution.

How much has been raised?

As of August 2023, LACMA has met and exceeded the campaign goal of $750 million.

How much is the construction cost per square foot?

The construction cost is approximately $1,400 per square foot, which is toward the low end of the range for new museum construction (the comparable national market range for new museum construction in major metro areas is $1,250 to $1,800 per square foot). Out of the $650 million budget, the total construction cost is approximately $490 million. $490 million divided by 347,500 square feet is equal to $1,400 per square foot.

Was there any debt issued for the new building?

Yes. Private donations are generally paid over a period of time. Therefore, as part of the plan of finance approved by LACMA’s Board of Trustees and the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, $300 million of debt was issued by the County of Los Angeles in November 2020 to be fully paid for by LACMA from private donations.

Will LACMA sell artworks to cover construction costs or pay debt?

No. LACMA will never sell art to fund construction, operating, or other costs.

Is LACMA reducing space for the permanent collection?

No. The new building gives us the flexibility to display collection areas for longer periods or to present permanent collections as temporary exhibitions, giving visitors opportunities to see more art from the permanent collection in greater variety. Additionally, LACMA has always displayed works from the permanent collection in special exhibitions in BCAM and the Resnick Pavilion, and will continue to do so. BCAM, Level 1 also exhibits some of our most treasured permanent collection works, such as Richard Serra’s Band and Robert Irwin’s Miracle Mile.

The new building has a lot of glass. Aren't museums supposed to avoid natural light?

Thousands of works in our collection (sculpture, tiles, ceramics, and more) can be safely displayed in natural light, and are in fact wonderful to view in that setting. The new building will have a range of exhibition spaces, from galleries with natural light to galleries with controlled artificial lighting. The majority of galleries in the new building are designed to be able to display light-sensitive works. Natural light and views to the park along the perimeter of the building also will reduce fatigue in our visitors.

Why are the gallery walls concrete?

Concrete was chosen to give the building a sublime aesthetic character and beautiful sense of gravitas. Concrete walls have been utilized successfully in other museums like the Kimbell, the Guggenheim, and Kunsthaus Bregenz. Not one artist whose work was displayed at Bregenz has ever covered that museum's walls with sheetrock. Additionally, many objects and antiquities in our collection originated in buildings or other settings built from stone, so it is particularly fitting to display them in concrete-walled galleries.

Will the new building be sustainable? What level of LEED certification will be achieved?

LACMA is committed to achieving as high a level of sustainable design, construction, and operating principles as possible. The project will incorporate LEED features achieving Gold certification. Excavated earth and demolished materials will be recycled to the fullest extent possible, and landscaping will require minimum water and conform to the natural flora of the area. Water conservation measures in addition to drought-tolerant planting may include a variety of features such as the installation of dual plumbing in order to use reclaimed water for toilet flushing, self-closing faucets, and storm water retention through cisterns in which water would be filtered, treated, and recycled for use in toilets, urinals, irrigation, and cooling towers. The new building will replace older, much less efficient buildings that did not meet current sustainability standards, and wasted scarce resources.

Will Urban Light be moved?

Urban Light will stay in place and visitors will continue to be able to enjoy the artwork.

Where would LACMA expand in the future?

LACMA is pursuing the next phase of its expansion through additional museum spaces across L.A. County, enhancing the accessibility of our collections and bringing art and art education to communities throughout our vast county. We already have ongoing exhibition, education, and public programming at Charles White Elementary School in MacArthur Park, collaborations with the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College in Monterey Park, and an additional museum currently being planned in South L.A. LACMA is also planning to participate in the SELA Cultural Center, designed by Frank Gehry, in Southeast L.A.

What is the timeline for the new building?

Construction began in 2020. The building is currently projected to be completed in late 2024.

What does the new building project entail?

The building project entails the construction of one modern and efficient building to replace four aging buildings (Ahmanson, Art of the Americas, Bing, Hammer), as well as the construction of a parking structure on Ogden Drive to replace the spaces on the previous Spaulding Avenue parking lot.

Why is LACMA replacing its old buildings?

The old buildings had many serious structural issues and problems with plumbing, sewage, lack of seismic isolation and methane mitigation, defunct waterproofing, and leaks, compromising their ability to host our visitors and staff and hold our collections.

Why couldn’t you repair the old buildings?

To retrofit the existing buildings would be extremely costly while still failing to provide the ideal setting for the collections and visitors. Almost 20 years ago, and again in 2014, the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors and LACMA’s Board of Trustees considered repairing the structures, and in both cases they found the retrofitting cost prohibitive. In 2014, the minimum estimated cost to retrofit just the visible deterioration was $246 million. New construction allows the museum to create both a safer building and new galleries designed to be more accessible, more functional, and more enjoyable.

Why are the galleries on one level?

The horizontal design offers an egalitarian experience of LACMA’s diverse collections. Displaying all art on a single level avoids giving more prominence to any specific culture, tradition, or era, offering visitors a multitude of perspectives on art and art history in a more accessible, inclusive way. The single-level gallery floor will also be more intuitive to navigate and easier to access, especially for wheelchairs and strollers, and its perimeter of transparent glass will provide energizing natural light and views to the park and urban environment, with views from outside into the galleries.

Why does the building cross Wilshire Boulevard?

The new building spans Wilshire in order to provide 3.5 acres of new park and outdoor space for visitors in Hancock Park and the Natural History Museum’s ongoing and future research. This public outdoor space will be home to even more public sculptures and is an invaluable resource in our dense urban community.

How big will the new building be?

The new building totals 347,500 square feet, replacing approximately 393,000 square feet of existing buildings. There will be approximately 110,000 square feet of gallery space, replacing approximately 120,000 square feet of gallery space. The building also includes a new theater, education spaces, three restaurant/cafes, a museum shop, and covered multipurpose event spaces. Much-improved ancillary and back-of-house facilities will support LACMA’s public programs, including two loading docks and enhanced security, facilities operations, visitor services, transit art handling, and more.

How did you reduce the size of the new building from the size of the existing buildings?

The reduction in total size from that of the existing buildings is made possible by moving functions not needed within the building itself: the museum has moved offices across the street, expanding our existing office space at 5900 Wilshire, and moved art storage out of Hancock Park.

How much will LACMA’s gallery space have increased in total once the new building is completed?

By the time the new building opens, we will have expanded our total gallery space from approximately 130,000 in 2007 to 220,000 square feet.

Does LACMA need more gallery space in its Wilshire campus?

LACMA’s Board of Trustees and the County Board of Supervisors believe that after doubling our exhibition space over the last decade, this is the appropriate size for our campus on Wilshire.

What is the budget for the new building?

Of the $750 million campaign goal, the total building budget is $650 million, which includes construction costs, soft costs, and contingencies. Of the $650 million, the construction costs (“hard costs”) are estimated at $490 million. A rigorous cost estimating and cost management process was followed throughout the preconstruction phase to be within budget and a guaranteed maximum price contract was signed with our general contractor, Clark Construction, in mid-2020, in line with our budget. The construction cost is in line with similar projects and the cost per square foot of LACMA's Renzo Piano–designed gallery buildings, BCAM and Resnick Pavilion (adjusted for inflation).

How is this new building being funded?

This building cost is funded through an unprecedented public-private partnership by which the new County-owned building will be 80% paid for by private donations. The County of Los Angeles has contributed $125 million and the rest came from private donations. The County will receive a 4:1 match for its contribution.

How much has been raised?

As of August 2023, LACMA has met and exceeded the campaign goal of $750 million.

How much is the construction cost per square foot?

The construction cost is approximately $1,400 per square foot, which is toward the low end of the range for new museum construction (the comparable national market range for new museum construction in major metro areas is $1,250 to $1,800 per square foot). Out of the $650 million budget, the total construction cost is approximately $490 million. $490 million divided by 347,500 square feet is equal to $1,400 per square foot.

Was there any debt issued for the new building?

Yes. Private donations are generally paid over a period of time. Therefore, as part of the plan of finance approved by LACMA’s Board of Trustees and the County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors, $300 million of debt was issued by the County of Los Angeles in November 2020 to be fully paid for by LACMA from private donations.

Will LACMA sell artworks to cover construction costs or pay debt?

No. LACMA will never sell art to fund construction, operating, or other costs.

Is LACMA reducing space for the permanent collection?

No. The new building gives us the flexibility to display collection areas for longer periods or to present permanent collections as temporary exhibitions, giving visitors opportunities to see more art from the permanent collection in greater variety. Additionally, LACMA has always displayed works from the permanent collection in special exhibitions in BCAM and the Resnick Pavilion, and will continue to do so. BCAM, Level 1 also exhibits some of our most treasured permanent collection works, such as Richard Serra’s Band and Robert Irwin’s Miracle Mile.

The new building has a lot of glass. Aren't museums supposed to avoid natural light?

Thousands of works in our collection (sculpture, tiles, ceramics, and more) can be safely displayed in natural light, and are in fact wonderful to view in that setting. The new building will have a range of exhibition spaces, from galleries with natural light to galleries with controlled artificial lighting. The majority of galleries in the new building are designed to be able to display light-sensitive works. Natural light and views to the park along the perimeter of the building also will reduce fatigue in our visitors.

Why are the gallery walls concrete?

Concrete was chosen to give the building a sublime aesthetic character and beautiful sense of gravitas. Concrete walls have been utilized successfully in other museums like the Kimbell, the Guggenheim, and Kunsthaus Bregenz. Not one artist whose work was displayed at Bregenz has ever covered that museum's walls with sheetrock. Additionally, many objects and antiquities in our collection originated in buildings or other settings built from stone, so it is particularly fitting to display them in concrete-walled galleries.

Will the new building be sustainable? What level of LEED certification will be achieved?

LACMA is committed to achieving as high a level of sustainable design, construction, and operating principles as possible. The project will incorporate LEED features achieving Gold certification. Excavated earth and demolished materials will be recycled to the fullest extent possible, and landscaping will require minimum water and conform to the natural flora of the area. Water conservation measures in addition to drought-tolerant planting may include a variety of features such as the installation of dual plumbing in order to use reclaimed water for toilet flushing, self-closing faucets, and storm water retention through cisterns in which water would be filtered, treated, and recycled for use in toilets, urinals, irrigation, and cooling towers. The new building will replace older, much less efficient buildings that did not meet current sustainability standards, and wasted scarce resources.

Will Urban Light be moved?

Urban Light will stay in place and visitors will continue to be able to enjoy the artwork.

Where would LACMA expand in the future?

LACMA is pursuing the next phase of its expansion through additional museum spaces across L.A. County, enhancing the accessibility of our collections and bringing art and art education to communities throughout our vast county. We already have ongoing exhibition, education, and public programming at Charles White Elementary School in MacArthur Park, collaborations with the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College in Monterey Park, and an additional museum currently being planned in South L.A. LACMA is also planning to participate in the SELA Cultural Center, designed by Frank Gehry, in Southeast L.A.

What is the timeline for the new building?

Construction began in 2020. The building is currently projected to be completed in late 2024.